-

“Not in our nature,” a poem

(This poem is about the parable “The Scorpion and the Frog” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Scorpion_and_the_Frog)

Nature embraces with all her ill,

The creatures being by her will,

Seduced by the scorpion’s cunning skill,

The frog and him were killed.The scorpion’s sting was in his nature,

The ultimate cause of the dictator.

How humans fight like gladiators

For fear of our behavior.The scorpion stung, the frog was fraught,

A lesson of nature’s punishment brought.

Yet men, endowed with rational thought,

Can act as they ought.But reason with instinct become a hindrance,

The guilt and shame for our existence,

As we may keep these sins at distance.

Then man and nature, different.

-

The Weil Conjectures: A tale of mathematics, philosophy, and art

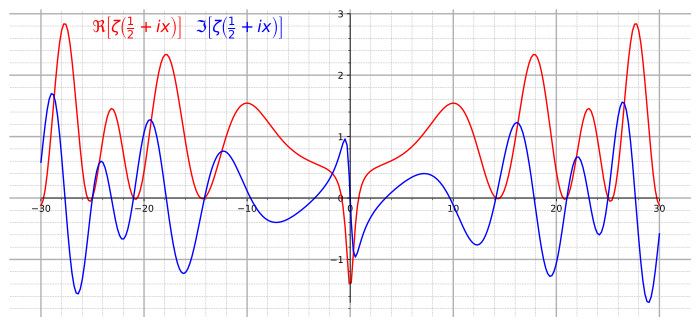

The real part (red) and imaginary part (blue) of the Riemann zeta function along the critical line Re(s) = 1/2. The first non-trivial zeros can be seen at Im(s) = ±14.135, ±21.022 and ±25.011. The Riemann hypothesis, a famous conjecture, says that all non-trivial zeros of the zeta function lie along the critical line. For some, mathematics much more than a matter of solving problems. It transcends abstraction and intellectual pursuit into a way of determining meaning from life. For a brother and sister, it can mean a relentless search for truth that reads like a Romantic fable. A history that consists of settings across time and space punctuated by individual actions and events, the novelist creates a narrative that sheds light on a new meaning of truth. Truth may be elusive, especially in a post-truth society, but, in a metamodernist manner, it’s closer to reality – an authentic, original reality – than it seems.

In Karen Olsson’s The Weil Conjectures: On Math and the Pursuit of the Unknown, she intertwines the stories of French brother and sister André and Simone Weil during a Europe in the midst of World War II. The former, a mathematician known for his contributions to number theory and algebraic geometry, and the latter, a philosopher and Christian mystic whose writing would go on to influence intellectuals like T.S. Eliot, Albert Camus, Irish Murdoch, and Susan Sontag. Hearkening back to the childhood of the siblings, we follow their stories studying poetry, mathematics, tragedies, and other artists and scientists. Between these glimpses of their lives, Olsson throws in her personal anecdotes studying mathematics as an undergraduate at Harvard. She describes a “euphoria” from thinking hard about mathematics such that, while knowledge itself is the goal, it’s a disappointment to reach it. You lose your pleasure and sensation in seeking truth once you find it. André characterizes his own search for happiness through this search for truth. Drawing parallels between herself and the siblings, their stories depend less on the context that surrounds them and more on the similarities in their narratives.

With multiple stories happening at once, the reader feels a sense of timelessness in the writing. The plot has less to do with one event happening after another, but more with a grand narrative carrying each part of the story with one another. A mix of elements of modernism and postmodernism together, Olsson’s book serves as a sign of the next step: metamodernism. In separate directions, mathematics and philosophy, the two venture for truth that seems to lie just outside their reach. Olsson tells the narratives through letters between the siblings, the notebooks upon which Simone scribbled her thoughts – philosophic, mathematical, and religious. On the purposes of mathematics and philosophy, Olsson questions how mathematics had become disconnected from the world around them. So focused on attacking problems in an abstract, self-referential setting, the field’s myopic focus on truth had strayed from meaning, she believed. Simone’s story through working in factories and a Resistance network with a wish to free herself from the biases of her own self would lead to her death by starvation in solidarity towards war victims.

If the labor of machinery is so oppressive, Simone wondered how to create a successful revolution technological, economic, and political. The pain she sought through suffering made her who she was. It humanized her as she wrote about the German army defeating France. The evil in the world was God revealing, not creating, the misery inside us. Simone sought to achieve a state of mind that liberated herself from the material pursuits of the world through philosophy and Christian theology. She wanted an asceticism to provide she could a morally principled life on her self-imposed rules. This included donating money during her career as a teacher so that she would earn the same amount as the lowest-paid teachers.

D. McClay, senior editor of The Hedgehog Review, wrote that Simone’s own struggle with Catholicism partly had to do with her anti-Semitism in his essay “Tell Me I’m OK.” “Though Weil was herself Jewish, she did not identify as Jewish in any significant sense, and her sense of solidarity with the oppressed did not extend to other Jews,” McClay said. Feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir who, according to her memoir, didn’t get along with Weil when they met, offers a contrast to Weil in how to live a good life.

In Beauvoir’s The Ethics of Ambiguity, she argued existentialist ethics are rooted in recognition of freedom and contingency, McClay said. Beauvoir wrote, “Any man who has known real loves, real revolts, real desires, and real will knows quite well that he has no need of any outside guarantee to be sure of his goals; their certitude comes from his own drive…. If it came to be that each man did what he must, existence would be saved in each one without there being any need of dreaming of a paradise where all would be reconciled in death.” Beauvoir’s atheism created friction with Weil, McClay said. They also define a reality of what we do in the world that defines their own “drive,” which seems like a response to the threats of existential nothingness.

McClay continued to compare the two Simones to provide an account for how to live a moral life, involving abandoning the idea of a “good person” in favor of goodness without regard to how others judge us. “It might mean living more like Weil—taking what you need, and giving away the surplus—”, McClay said, “with the caveat that one takes what one actually needs.” Beauvoir and Weil, moral philosophers that describe how “we are always, simultaneously, together and alone,” may even be guides for the crises of our age. Living together and alone, through the community of one another and the isolation of intellectual work, we can live like Weil intended. McClay’s writing also shows this mix of modernity’s unified, centralized identity withothers with postmodernism’s decentered self.

Interspersed in Olsson’s book are stories about Archimedes’ having “eureka” moments, René Descartes’ search for the “unknown” (x in algebra), L. E. J. Brouwer’s work in topology, and even the mathematician Sophie Germain who studied mathematics in secrecy and corresponded with male mathematicians under a pseudonym. Tracing the foundations of mathematics, language, and other tenets of society to the Babylonians, she carefully compares the methods of problem solving and invention using language to reveal deeper nature of the phenomena (“Negative numbers infiltrated Europe during the Middle Ages” making mathematics seem deceptive or insidious) or method in discovery (“Are numbers real or not? Were they discovered or invented? We pursue this question for a couple of minutes.”). The figures comment on their own judgements on the deeper meaning and purpose in their work such as George Cantor saying “I see it, but I do not believe it.” Olsson drops these quotes and glimpses of history in between moments of trials of other characters.

When the early 20th-century Jewish-born mathematician Felix Hausdorff set the grounds for modern topology, an anti-semitic mob claiming they would send him to Madgascar where he could”teach mathematics to the apes” gathered around his house. Olsson then switches to her perception that she always read André and Simone Weil’s last name as “wail,” despite it actually pronounced as “vay.” Then, Olsson returns to Hausdorff’s story of taking a lethal dose of poison after failing to find a way to escape to America. In a farewell letter to his friend Hans Wollstein, who would later die in Auschwitz, Hausdorff wrote “Forgive us our desertion! We wish to you and all our friends to experience better times.” Olsson’s juxtaposition of the “wail” last name alongside the Kristallnacht, a systematic attack on Jews, compares the personal struggles of André and Simone as inseparable from the Nazi’s persecution of Jews – as though the siblings were “wailing” in response to their persecution. It also emphasizes Olsson’s own perception of the siblings that, no matter how hard she tries, she still has her own take on the story. Even when she shares the rise of Nazis in Europe, Olsson’s limited perspective preserves the postmodern disunity of culture alongside a modern master narrative. The art of narration is both a process of Olsson’s own struggles to share and an authenticated, objective authority of knowledge that can forgive Hausdorff’s suicide and provide a better future for everyone.

With Descartes’ discovery of the “unknown,” he also introduced methods of standard notation of mathematics that would let researchers use superscripts (x² as “x squared”) and subscripts (x₀ as “x naught”). Olsson demonstrates the similarities between the methods of reasoning that let mathematical invention become the same engine underneath the creation of science, art, and literature, as French mathematician Jacques Hadamard explained. Hadamard’s interest of what goes on in a mathematician’s mind as they do what they do was also in response to the crisis of modernity having witnessed the horrors of both world wars. The mathematician frequently seek new ways of looking at problems in mathematics as researchers came and visited during seminars twice a week. The pieces of each story come together in a flow that uses a variation in style, length, and meaning to create a multidimensional work of art that is the book. Each passage flows seamlessly in the interplay between exposition and narrative, description and action, showing and telling.

At one point, Simone and André’s reading habits are interrupted by the narrator of Clarice Lispector’s Agua Viva proclaiming mathematics as the “madness of reason.” The rational, coherent, commonsense nature of mathematics would seem to contradict the foolish wildness of madness. But, as an interruption to Simone’s love of Kant and Chardin as a child and André’s interest in the Bhagavad Gita in college, this “madness of reason” becomes more apparent. In Why This World: A Biography of Clarice Lispector, Benjamin Moser wrote:

My passion for the essence of numbers, wherein I foretell the core of their own rigid and fatal destiny,” was, like her meditations on the neutral pronoun “it,” a desire for the pure truth, neutral, unclassifiable and beyond language, that was the ultimate mystical reality. In her late works, bare numbers themselves are conflated with God, now without the mathematics that binds them, one to another, to lend them a syntactical meaning. On their own, numbers like the paintings she created at the end of her life, were pure abstractions, and as such connected to the random mystery of life itself. In her late abstract masterpiece Água Viva she rejects “the meaning that her father’s mathematics provide and elects instead the sheer “it” of the unadorned number: “I still have the power of reason-I studied mathematics which is the madness of reason-but now I want the plasma-I want to feed directly from the placenta.

The Renaissance depiction of madness as an intrinsic part of man’s nature is found in the literature and philosophy of the time period. An imbalance, or excess, of reason could lead to the madness that seeks this mysterious, “pure truth” that transcends language itself. Much the same way Simone and André seek the essence through different forms of this “madness.” Simone’s personal battles with health and existential issues seem more alike a mathematician’s search for reason. Olsson later mentions the “madness of reason” as she narrates her own lonely experience “trying to demonstrate small truths” an undergraduate in her lonely dorm room on a cold, wintery day. It’s a localized truth that Olsson finds in her work, but still remains part of a grander narrative that connects their stories. The interjecting quote from Lispector’s text highlights this search for truth in the stories of Simone, André, and Olsson herself.

According to Olsson, Descartes used “x” to refer to the unknown because the printer was running out of letters, but there may have been an aesthetic choice in addition to the pragmatic use. “x “ would come to mean that which we don’t know in other contexts such as sex shops and invisible rays. Olsson continues her personal story asking the question “What is my unknown? My x?” She narrates her venture back to mathematics after writing novels in her time since she graduated from Harvard University.

Olsson emphasizes Simone’s inferiority complex to her brother as one of the primary causes for this perspective on the world. Simone’s own desire to be a boy, use the name “Simon,” and absence of any lover while André proposed the Weil Conjectures, married, and had children show these contexts. She found truth in this suffering and disregard for material pleasures – even chasing states of mind in which she could perceive the world in a state of purity and without any biases of her own self. The conjectures would become the foundation for modern algebra, geometry, and number theory.

When Olsson took a course under Harvard mathematician Barry Mazur, she didn’t dare speak to him. The conjecture, Mazur explained, would lay down the basis of a theory, expectations believed to be true, driven by analogy. Olsson still recalls her feeling of awe when she first learned and geometry and the power of understanding the world without memorizing it. After André was arrested while on vacation in Finland in 1939 on suspicion of spying, he barely missed execution when a Finnish mathematician suggested to the chief of police during a dinner before the day of the execution to deport him instead. While André is forced by train to Sweden and England, Olsson returns to her childhood excitement in middle school learning about “math involving letters.” She then recalls moments teaching her two-year-old daughter how to count as the child asks “Where are numbers?” When Olsson returns to André’s story, now as he’s transferred to a prison in France and requires unidle intellectual activity, she comments that escaping France was a more pressing problem than anything in mathematics.

As André longs for an ability to engage in research even in the cloistered sepulchre of a prison cell, he writes to Simone comparisons of mathematics to art. Simone is allowed to visit him for a few days a week, and the two rassure each other that they’re okay. André tells Simone he told an editor to send page proofs of his article to her so she can copyedit them. The writing between the two goes into stories of Babylonians and Pythagoreans reminiscent of the dialogue the two siblings had as children. Olsson’s own story intertwined with the communication between Simone and André serves as a parallel to demonstrate that she, too, can make mathematics accessible to the common person the same way Simome did with André’s work. André’s colleagues would even start to envy the quiet solitude of prison in which he could produce work undisturbed. Comparing mathematics to art, though, André described the material essence of a sculpture that limit a mathematician’s objectivity while remaining an explanation in and of itself. In this sense, it has both objective and subjective value the same way a mix of modern and postmodern story would. Simone doubted this, though. Works of art that relied on a physical material didn’t directly translate to a material for the art of mathematics. Though the Greeks spoke of the material of geometry as space, André’s work, Simone argued, was an inaccessible system of previous mathematical work, not a connection between man and the universe.

The brother responded with the role of analogy in mathematics far beyond a mental activity. It was something you felt, a version of eros, “a glimpse that sparks desire,” Olsson wrote. Going through the history of mathematics from the nineteenth-century watershed time in which questions of numbers were solved using equations, the mathematician feels “a shiver of intuition” in connecting different theories. Simone would imagine societies built upon mathematics, mysticism, and existential loneliness. Through this, all of Olsson’s jumping between stories becomes clear. She had set the reader up to view mathematics as an art the way André did and, through the world Simone created, something the general audience could understand. Olsson continues with her personal experience as an undergraduate being recommended by a professor to write about mathematics for a general audience as a career alongside dream sequences of André and Simone.

In 1938, Simone attended a Bourbaki conference, a group of French mathematicians that André had initiated with the purpose of reformulating mathematics on an abstract and formal, yet self-contained basis. The mathematicians would sign their names collectively as “Bourbaki” on papers as they attempted to unify contemporary mathematics with a common language just as Euclid did centuries ago. While the group members would yell at one another with hard-hitting questions, even threatening at times, Simone began to believe that mathematics should be made more accessible to a mass audience. The Bourbaki group’s vision lead them to describe hundreds of pages of set theory before defining the number 1. They sought to create an idea of mathematics as a system of maps and relationships that were more important than the intrinsic qualities of numbers and other mathematical objects themselves. Scientific American would call André “the last universal mathematician.” This method of universalizing while still emphasizing relationships among objects shows a modernist tendency, the former, interacting with a postmodernist one, the latter.

Olsson’s own stories through studying mathematics as a student and teaching her children She explains the highlight of her mathematics career was finding the answer to a course problem before one of her classmates did. Her humility and sense of humor make her writing all the more approachable and relatable.

The book’s weakness is that the individual stories feel abbreviated at times. Olsson switches back and forth between many narratives that may leave the reader feeling confused or even frustrated that desires and beliefs of the characters are unexpanded. It can make it difficult to get committed to the story events or feel connected to characters when their moments are so brief and spread out across the book. The short snippets of stories across time and space alongside Olsson’s juxtaposition of them with one another make the reading easy to understand for anyone without a strong background in either mathematics or philosophy. Still, much the same way Olsson describes the search for truth, it leaves the reader in a perpetual search. We get a feeling of excitement that we are bound to get to the correct answer to a problem or find meaning in research while still never quite achieving it.

Olsson’s book serves as a beacon of the power of evidence and justification in a post-truth world. Olsson addresses the constant searches for truth and meaning in our current society by capturing opposites and extremes in her writing. The empirical, hypothesis-driven mathematics and speculative, argument-driven philosophy contrast one another on the meandering search for truth. The isolation of intelligence for both André and Simone in their work contrast the warmth of community and social engagement the two find in their respective environments. Truth becomes less of something that we must obtain by being on one side or the other and more of finding appropriate methods of addressing problems. It’s objective in that it lies in the techniques of various disciplines, but constructed because it comes from the individual’s choice. In a typical mix of modernism and postmodernism, Olsson’s personal story to find the answers to her personal curiosities by turning back to mathematics demonstrates this mix of the personal with the impersonal.

Like postmodern stories, Olson’s book is non-linear and reveals truth as a series of localized, fragmented pieces. Like modernism, we find greater purposes and narratives between the different stories as a testament to the power of science and technology. It switches between the progressive, exalted story of André with the melancholic, tragedy of Simone with parallels between the stories together. The grand themes of the power and style of mathematics and philosophy dictate the rules and principles that set the foundation for the stories. André’s story and Simone’s may even be treated with the former as a modernist tale of the triumph of science and the latter, a postmodern warning of society’s so-called “progress.” In regular metamodernist fashion, Olsson uses elements of both modernism and postmodernism in her book. In metamodernist fashion, the two searches for truth become one and the same. Philosophy may ask “Why?” but, for mathematics, the question is “y₀?”

-

Neuralink: the allure of brain-computer interfaces

“You better be careful telling him something’s impossible. It better be limited by a law of physics or you’re going to end up looking stupid.” – Max Hodak, Neuralink president As the gap between humans and computers becomes smaller every day, the startup Neuralink, backed by figures including Elon Musk, Vanessa Tolosa, and other individuals, recently hosted a public conference in which they revealed their efforts create neural interfaces between brains and computers. The futuristic dream of a brain-computer interface for mutual exchange of information between humans and works of artificial intelligence may sound like something out of a science fiction dream, but the neural interface, a device to enable communication between the human nervous systems and computers, would include invasive brain implants and noninvasive sensors on the body.

During the livestream on July 16, 2019, Neuralink revealed their work to the public for the first time with the pressing goal of treating neurophysiological disorders and a long-term vision of merging humans with artificial intelligence. With $158 million in funding and nearly 100 employees, the team has made advances in flexible electrodes that bundle into threads smaller in width than human hair inserted into the human brain. As the computer chip processes brain signals, the first product “N1” is meant to help quadriplegic individuals using brain implants, a bluetooth device, and a phone app.

In their paper “An Integrated Brain-Machine Interface Platform with thousands of channels,” Musk and other team members noted that electrode impedances after coating were really low allowing for efficient information transmission. Each electrode uses pixels at 3 Hz bandwidth to measure spikes, a neuron’s responding to stimuli that are generally about 200 Hz but can reach up to 10 kHz at times. The dense web that the team creates would let them feed the entirety of a brain’s activity to a deep learning program for creating artificial intelligence at a great degree of accuracy, study the neuroscientific basis for phenomena, or even decode the basics of other features such as language. For the Human Connectome project, an initiative to create a complete map of the human brain, Neuralink’s scale would give more precision than the project has done before.

This precision could address the ethical issues raised when the cognitive response of a brain-computer interface doesn’t appropriately match what a patient communicates. Neuralink’s work should take into account the risks associated with such a fine level of precision. Most strikingly, brain-computer interfaces so intimate to who we are raise the ethical issues of whether neurologically compromised patients can make informed decisions about their own care. Philosopher Walter Glannon said in his paper “Ethical issues with brain-computer interfaces,” the capacity to make decisions is a spectrum of cognitive and emotional abilities without a specific threshold that would indicate how much constitutes the ability to make an informed decision. Just as philosophers and ethicists have studied the basis for ethical frameworks in the decision-making process among physicians, patients, and other roles in health care, the complex semantic processing of brain-computer interfaces may not constitute enough to show a patient has the cognitive and emotional capacity to make an informed and autonomous decision about life-sustaining treatment. It would need some a behavioral interaction between the patient and the health care professional so that the brain-computer interface’s response reflects only what it’s capable of communicating.

Tim Urban of “Wait But Why” described Neuralink as Musk’s effort to reach the “Wizard Era” – in which everyone could have an AI extension of themselves – “A world where AI could be of the people, by the people, for the people.” The promise of cyborg superpowers as humans step into the digital world calls back to science fiction stories such as 2001: A Space Odyssey and Jason and the Argonauts. From the electrode array that joins the limbic system and cortex of the human brain gives Nerualink the information for those regions of the brain. It creates a reality in which information and the metaphysical nature of what we are depend less on the physical structures of the brain itself, but, rather the information of the human body. Prior to artificial intelligence, the brain evolved to develop communication, language, emotions, and consciousness through the slow, steady, aimless walk of natural selection, and a collective intelligence that can contribute to machine learning algorithms like Keras and IBM Watson. The Neuralink interface would let us communicate effortlessly with anyone else in the collective intelligence. The AI extension of who are means that the machines that are built upon this information are part of us as much as they are machines. With machines connecting all humans, we achieve a collective intelligence that goes against how human and animal minds have evolved over the past hundred million years.

-

Appearing suspicious may come at a cost

Suspicion by Gültekin Bilge How do you trust others? What makes you become suspicious when working with other people? Though we rely on collecting information about others when making decisions, the ways we collect that information may change how others perceive us. People may be less likely to trust others when they inquire about their behavior in a way that appears suspicious, a new study shows.

Decisions of whether to trust other people can vary based on risk and uncertainty. In simulating how people trust one another using a game between trustees and investors, researchers studied social context, monetary cost, and the trustee’s trustworthiness to show that an investor appearing suspicious may lessen trust and appearing averse to betrayal, increase trust.

Using computational models of how individuals collecting information before making an investment decision, the researchers examined the intuitive patterns behind why participants made the decisions they did. They tested participants under conditions of whether collecting information cost money and whether the trustee would know the investor was collecting information. Participants gathered less information when it came at a cost and when they could find conclusive results from the information about others.

The researchers tested various model to determine which one fit the experimental results best. When the difference between outcomes that would favor investing was different enough from those that wouldn’t, participants stopped collecting information. To test how strong of a role suspicion played in these decisions, they compared the Cost of Appearing Suspicious (CAS) model against a Sample Cost model, an Uncertainty model, and a discrete Drift Duffusion Model (dDDM). For the CAS, Sample Cost, and Uncertainty models, the participants’ decisions are Bayesian in the sense they determined how likely they are to invest based on their previous beliefs about either the trustee or the investor.

The CAS model used a suspicion factor, that gathering information decreases the probability of investment. The Sample Cost model does not use this suspicion factor, and, under the Uncertainty model, participants would stop when the posterior belief distribution width dropped below a tolerance threshold. Under the dDDM, on the other hand, participants would collect information until their evidence for trustworthiness or untrustworthiness met a certain criteria. After determining how well models fit various conditions on the individual level, they found the CAS model predicted better than the others, and it even fit well to investment decisions after collecting information.

When individuals choose to invest or not, scientists have proposed various models for decision-making across different contexts. They come into play as people choose whether to work with or trust others. One study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showed, when people work together, they care about whether their partner gathers information about how much they would profit if they defected. They instead engage in blind cooperation cooperate among trustworthy and untrustworthy people, but don’t collect information to make themselves appear suspicious. This is further shown that people are perceived as selfish when they gather information for their own profit in a study in the Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics.

The work has practical applications in information collection and use for psychiatric disorders. Biases in collecting information when information is uncertain or scarce has been associated with weighing negative information heavily in depression and compulsivity. How well we model the moral character of other individuals are central to disorders like borderline personality disorder and autism.

-

How the brain makes things simple

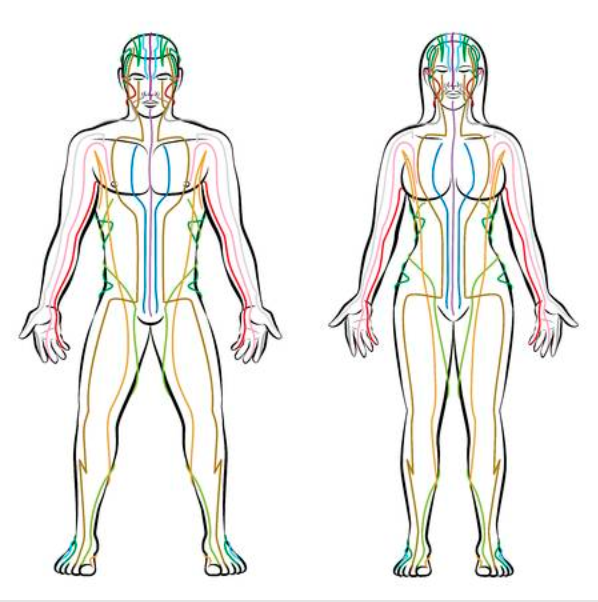

The homunculus depicts how the body represents itself in the somatosensory cortex of the brain. Physical tasks the may seem basic to humans can be much more complicated for machines. The sheer number of degrees of freedom and dimensions the brain must use to make something as versatile and complex as hand motions means that the brain must reduce these high-dimensional spaces to achieve these feats of motion. This is a method of taking complicated processes such as the movement of individual fingers and finding ways of classifying these movements so that they may be accessed without as much information as they would otherwise take. Computational neuroscientists Yuke Yan and James G. Goodman along with biologist Sliman J. Bensmania observed the musculoskeletal movements of human and monkey hand kinematics during sign language, typing, and grasping objects with a principal component analysis. This let them figure out how the motions were specific to certain conditions such as the object trapped or the letter signed using linear discriminate analysis to classify different conditions.

They removed components in descending order of variance by reconstructing the hand posture on each trial and classified them using linear discriminant analysis to determine how many experimental results could be classified correctly. This let them determine the functions of complicated hand gestures using a small number of variables that represent the various motions. Using combinations that account for the motions, this would let researchers understand how such intricate, complicated motions can be governed by a set of neurons or neurophysiological mechanisms. They tested how similar the results were between humans and monkeys and found monkeys had hand postures that weren’t as specific for different objects.

Finally the researchers classified hand motions using spike counts of neurons in the primary motor cortex to determine which ares of the brain corresponded with different motions. This gave them an overarching picture from neuroscience to behavior in how the brain makes sense of complicated, concerted movements.

Other methods of taking advantage of the probability let scientists create maps that can measure across variables in space. One may use a stochastic process, a family of random variables, on a space of probabilities to choose appropriate parts of the space that correspond with different outcomes. This can be applied from simple axon models of individual neurons to entire neural networks.

Very little is known about exactly how the brain interprets somatosensory activity as a particular tactile sensation. Some initial evidence towards understanding this comes from individuals with brain damage due to stroke. Researchers studying the somatosensory cortex of the brain, the part linked with tactile localization, have shown that hands and forearms tend to mislocalize sensations of touch towards their centers in healthy individuals and those who have had strokes in somatosensory regions. Psychologists Janellen Huttenlocher and Susan Duncan and statistician Larry Hedges proposed that spatial locations bias towrds the middle of categorical spaces and away from boundaries the more uncertain their information is. This method of dealing with uncertainty is another example of how the brain simplifies problems when it needs to.

Flies and humans use coding strategies when processing visual information to create more-refined images. Fly and cone photoreceptors respond to light by adapting their gain to a local mean intensity. This creates a contrast between intensity at the receptor and the local mean. The receptors then code the response to this contrast among all the values of input light. This way, the nervous system simplifies intensities to proportions that are more easily evaluated by the neuron’s response range. It also lets the fly or human identify same objects under different lighting.

-

A machine learning approach to Traditional Chinese Medicine

Modern science can uncover ancient wisdom. While it may seem regressive or pseudoscientific to study concepts from Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), they reveal deeper meanings about who we are as humans when subject to scrutiny by the scientific method. The herb formulas, plant-derived nature produces of TCM are still used in disease prevention and treatment despite the dominance of modern science. When medical researchers performed machine learning classification methods on 646 herbs are according to organ systems, known as Meridians, they found the 20 molecule features were most important for predicting these Meridian. It included structure-based fingerprints and properties of absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. As the first time molecular properties of herb compounds have been associated with Meridians, this provides molecular evidence of Meridian systems.

The Meridian system dictates how he life-energy qi flows through the body. Qi includes actuation of the body, warming, defense again excess, containment of body fluids, and transformation between qi and food, drink, and breath. Each Meridian corresponds to a yin yang quality, an extremity (hand or foot), one of the five elements (metal, fire, earth, wood, or water), an organ (such as heart or kidney), and a time of day. The yin yang qualities describe how complementary, opposite forces of the universe interact, such as Greater Yin or Lesser Yang. Given these roots in traditional, non-scientific thought, scholars have debated the scientific justification behind why and how TCM works. In their paper “Predicting Meridian in Chinese Traditional Medicine Using Machine Learning 2 Approaches,” the researchers assumed Meridian can be found through scientific methods to begin with. The five elements are qi are metaphysical, not modern physiological or medical phenomena. The researchers emphasized the need to examine the herb medicine actions as they relate to disease etiology to create a formal understanding of TCM.

Qi and yin yang as they relate to human health date back to texts of discussion and debates from the Warring States period (475–221 BC) of ancient China. Philosopher Zhaunghzi noted qi was the basis of the body’s physical being with the six qi (wind, cold, summer heat, fire, dryness, and damp) in harmony with one another as they affect the seasons. These theories would be used in medicine to describe relations and analogies between the body, the state, and the cosmos, or the universe.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.