Tag: Philosophy

-

Cross-examining Neuroscience

Moreso than most fields of science, neuroscience has very much a humane element in that what neuroscience says about the mind plays a central role in what makes us human. Our understanding of the brain spans strategies from naïve reductionism to cogito ergo sum. Are we computers or animals? Do our thoughts control us or do we control them? How does the reasoning of one person differ from another? But, in all the places these questions have shaken our self-understanding, the courtroom invites the greatest minds to bring justice from ethics, law, science, and everything else. How does neuroscience fare in the legal system?Before I continue, I must confess I know next to nothing about how much of the law works. Most of my understanding of the judicial system comes from watching “My Cousin Vinny” and playing Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney. However, My interest in the issues scientists and physicians face comes from something more fundamental than what a lawyer thinks. It should be about what should be right and wrong. I hope this ethical examination of the biggest dilemmas in neuroscience could focus more on what people “should” do rather than what people “can” do. In other words, before we can come to a conclusion of whether or not something is illegal or not, we must take a look at the ethical understanding of neuroscience.

“Uh… everything that guy just said is bullsh*t… Thank you.” The relationship between neuroscience and philosophy has always been tense. It would be far too easy to attribute much of who we are to the physical phenomena in the brain without paying attention to what ethicists and philosophers have written on morality.

But our scientific understanding of the brain shouldn’t detract from any philosophical concept of free will. While science is able to explain anything about empirical, observable phenomena, the fundamental metaphysical framework of free will and the self remain underneath. Is it really true that our advances in biochemistry and neuroscience will change and possible our concepts of free will from philosophy? The issue that persists in courtrooms is that many contemporary philosophers argue that we only have physical freedom, as in, our free will only goes so far as to what our bodies are physically capable of doing. And, as neuroscientists continue to crack the code of the brain, some scientists have asked, “If everything is just a product of physical phenomena in the brain, how can we hold people responsible for anything?” We might need an understanding of neuroscience to enter the political and legal sphere for us to account for even the slightest of bias, cognitive or otherwise, that might impair our judgement. Neuroscientist David Eagleman suggests this deeper understanding of the mind could explain much of our behavior, and, through this, we can determine a person’s responsibility his or her actions (e.g., someone predisposed to a specific mental disorder might not be criminally guilty for committing a certain crime.)

While using neuroscience to gain a better understanding of who we are is fine and dandy, things get complicated rather quickly. If a murderer had an abusive childhood, does that excuse him from responsibility of his actions? What about mentally ill criminals who, not only lack, but are physically unable to empathize? And, even if there are physical bodily responses that govern behavior, why should that stop at the uncontrollable forces within our neurons? What if the cause extended further, down to our own thoughts? Despite cries to end the idea of a “psychosomatic illness,” it’s certainly true that, when one imagines him or herself standing on the edge of a cliff, he or she experiences a physical response akin to the situation itself (e.g., sweating, rapid breathing, etc.) Does this mean that our own thoughts can control physical responses, and, in turn, control our behavior in this way, too? As the answers turn cloudy, it becomes clear that we can’t completely replace our notions of free will and responsibility with what neuroscience tells us about the physical connections in the brain. Before the brain can tell us what we’re culpable of in the courtroom, we should find a system of relating neuroscience with ethics.

In order to do this, neuroscience research should become more ethically-focused and succumb less to the whims of other influences such as the government groups. Dr. Miguel Faria, Professor of Neurosurgery and Associate Editor in Chief of Surgical Neurology International, says neuroscientists should “adhere to a code of Medical Ethics dictated by their conscience and their professional calling — and not imposed by the state.” In addition, Faria warns of an authoritarian future in which the government has usurped scientific knowledge for its own purposes. He says, “Our modern society, not even in democratic self-governance, to say nothing of authoritarian systems, has not advanced in ethical or moral wisdom to deal with the problems emanating from the technical and social ‘progress’ of the age.” While a self-serving solution of discerning the defendant’s responsibility based on his or her brain patterns might seem seductively plausible, a government-run nightmare looms around the corner. In the face of these threats, it’s up to scientists, the masters and diplomats of their own crafts, to make a statement to the world about what’s important.

Maybe the fight between the forces of good and evil comes down to the matter of grit.

No, not that kind of grit. No matter how hard we try to fight justice, it’s far more important for us to remain strong within ourselves about who we are. While the debates rage on, the grit that drives us to keep trying might someday save the neuro- disciplines from brain-bashing and help lawyers get their paperwork together. Until then, the jury’s out.

-

Protecting the Privacy of Mental Health Data

The paranoia of everyday life Read this article in the Indiana Daily Student here….

When speaking about the rights of an individual to his/her personal information, it’s easy to overlook the “personal” nature of mental health data. And, within the rhetoric of mental health, we spend a lot of time expressing the behavior, feelings and thoughts of those who suffer from mental illness, but we forget about the a deeper issue: who should know about it?

How much can more data actually help us? With so much information about ourselves, it’s easy to be misguided. Some, like Jesse Singal of NYMag’s “Science of Us,” have decried the calls of certain mental health issues at universities tremendously serious, yet suffering from confirmation bias or similar statistical fallacies. [6] If anything, we might just well be overwhelmed by how much we know about ourselves scientifically that we forget the humanistic aspect of ourselves. Basic science research in psychiatry hasn’t reached the goals it has claimed to make over the past few decades. Will turning to the social sphere, like Insel suggests, do any better?As science and medicine call for greater access to information for the purpose of research and clinical treatment, privacy becomes an issue. When we collect information from an individual, whether it’s a medical record from a hospital or a meeting with a school therapist, we have to protect his or her rights. How can we make sure data doesn’t fall into the wrong hands? What if a scientist’s data is used without permission or for unintended purposes?

“But we would want you and your family members…to take part because we want to have that information…And that’s obviously also going to be very sensitive but very important because it’s such a problem in this country.” – Francis Collins[7]

References:

[1] http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/16/health/tom-insel-national-institute-of-mental-health-resign.html

[2] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/answer-sheet/wp/2015/11/12/the-astonishing-amount-of-data-being-collected-about-your-children/

[3] http://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/new-prize-competition-seeks-innovative-ideas-advance-open-science

[4] http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/understanding/special/mhguidance.html

[5] http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/push-use-human-genome-make-medicine-precise/

[6] http://nymag.com/scienceofus/2015/11/myth-of-the-fragile-college-student.html#

[7] http://thedianerehmshow.org/shows/2015-09-28/nih-head-francis-collins-on-new-efforts-to-use-medical-records-of-volunteers-to-treat-diseases

[8] http://www.thestar.com.my/story/?file=%2f2008%2f10%2f15%2fcentral%2f2246634&sec=central

-

Mental Illness as a Language

Read this article in the Indiana Daily Student here….

Read this article in the Indiana Daily Student here….Mental health is an increasingly important issue. The World Health Organization estimates mental disorders will have become the world’s largest cause of death and disability by 2020. [3] Alongside this, we’ve put forth tremendous effort to understand our mental health from a scientific point-of-view. Our post-Enlightenment positivist view of scientific happiness has exponentially grown in accuracy. Though we’ve been doing this since the eighteenth century, in recent years, we’ve become more and more observant and critical of how our minds truly function in the scary world. All of our actions, behaviors, and moods can be measured down to a very fundamental level. But these efforts ignore the socio-political and cultural tendencies that have driven mental health over the centuries. In spite of this, it’s no wonder mental illness is on the rise.

Still, some criticize the field of psychiatry for being scientifically backwards. But far more insidious is the cultural deafness. Many of us have forgotten the role culture plays in mental health because we have tried to only use science to explain mental health.[1] However, our knowledge of the brain is is still very far from explaining mental disorders. We should remember the symptoms of mental illnesses are, not only scientific issues, but also a language through which we express ourselves. And we need to understand our culture and history to figure out what our distressed unconscious tries to tell us.[1] Maybe mental illness is not a “harmful defect we shun” and more a way we understand who we are. Seen this way, the mental issues we face are less of “biological flaws” and more of ways we express ourselves in society.

Speaking of the 21st century, our anxieties and insecurities are probably more philosophically and existentially grounded than we like to think. Many of us struggle with the postmodern irony and individualism that simultaneously shuns tradition while embracing conformity. Some of us call ourselves “introverts” as a form of self-identification to internalize some of our behaviors as “natural” or “acceptable.” We look at all the other amazing introverts and find some sense of belonging. But labeling ourselves just covers up who we really are. Others among us chase ideas and culture in hopes that we can find something unique about ourselves, that separates us from other people, but we’re only sharing the same social assumptions about what defines us.

The same way culture fashions us to understand aesthetics, value, ethics, and other humanistic qualities, our struggles with the emotions of mental illness could be the way our bodies understand the world. Einstein himself found solace, not only in science and art, but in the philosophical work of Schopenhauer, as he wrote on Planck’s 60th birthday:[4]

To begin with, I believe with Schopenhauer that one of the strongest motives that leads men to art and science is escape from everyday life with its painful crudity and hopeless dreariness, from the fetters of one’s own ever shifting desires. A finely tempered nature longs to escape from personal life into the world of objective perception and thought; this desire may be compared with the townsman’s irresistible longing to escape from his noisy, cramped surroundings into the silence of high mountains, where the eye ranges freely through the still, pure air and fondly traces out the restful contours apparently built for eternity.

Maybe our searches for “objectivity” of understanding mental illness are caused by these similar desires that motivate scientist. In this sense, our mental health is the way we search for meaning and satisfaction in the world.

All the world’s a stage, And all the mentally ill merely players.

References

[1] http://www.psmag.com/books-and-culture/real-problem-with-dsm-study-mental-illness-58843

[2] http://mh.bmj.com/content/28/2/92.full

[3] https://newhumanist.org.uk/articles/4934/the-cost-of-happiness

[4] http://www.neurohackers.com/index.php/fr/menu-top-neurotheque/68-cat-nh-spirituality/99-principles-of-research-by-albert-einstein

-

Elegance in science

The world thus exists to the soul to satisfy the desire of beauty. This element I call an ultimate end. No reason can be asked or given why the soul seeks beauty. Beauty, in its largest and profoundest sense, is one expression for the universe.

– Ralph Waldo Emerson (“Beauty” from Nature, published as part of Nature; Addresses and Lectures)If beauty is the expression for the universe, then it lies in the eye of science. Our scientific endeavors toward understanding the beauty of nature might even tell us something about ourselves.

If you asked me “What is the most beautiful thing in science?” I would probably respond with Maxwell’s equations. Named after the 19th-century Scottish scientist James Clerk Maxwell, these four equations are one of the most elegant ways to describe the fundamentals of electricity and magnetism. The first equation describes the electric field in relation to charge. Electric field tells us how an electric charge will affect other charges. The second equation explains magnetic flux, or how magnetic substances affect one another. The third equation tells us the electric field associated with this magnetism, and the fourth is about how the electric field changes due to the magnetic field. We can use these equations to form complex relationships in order to describe physical phenomena like the Earth’s magnetic field and the charges of elements. We can use them in a wide spectrum of physics and engineering feats from circuitboards to lasers. We can describe theoretical situations of point charges in empty vacuums through models and simulations. And, because of the concise way in which we can write these four equations, they’re an object of beauty by scientists. The fact that so much information can be conveyed in four equations is a testament to the elegance of science.

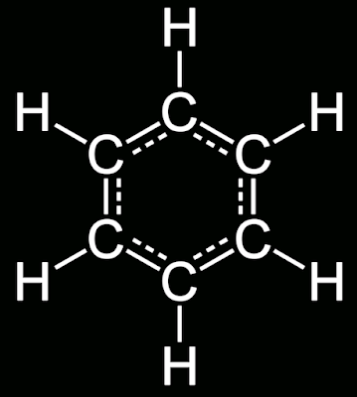

“Elegance” describes how we can explain complicated ideas in simple ways. Often cherished by mathematicians and physicists (but, on occasion, by biologists and chemists), elegant phenomena may be “beautiful” in that we can express more information, theories, or anything else using a small number of words, symbols, or lines of code. In this way, scientists look for elegance as a form of beauty, as an end goal that has aesthetic and practical value.The chemical compound benzene is very elegant, too. When the 19th century organic chemist August Kekulé had a dream about about a snake eating its own tail (much like the Greek serpent Ouroboros), it occurred to him that the structure of benzene must, similarly, have been a ring of carbon atoms in a hexagonal structure. The simplest of aromatic structures with one hydrogen atom for each carbon atom, benzene lays the foundation for applications in gasoline, plastics, synthetic rubber and industrial solvents. The symmetry and utility of this structure is an evidence to the imagination that chemistry allows. Though elegance is not as frequently used as an end goal in chemistry as much as it is in physics and mathematics, arranging atoms of different elements into bigger and bigger structures carries the idealistic, romantic notion that we can make sense of the complicated from the simple. In this sense, there is elegance through such intuitive explanations of the matter that makes the world. heritage.

There is simplicity in that the structure of DNA can give rise to phenomena with only four different nucleotide bases at the fundamental level. Why do we love brevity? Perhaps it’s practical and easy to measure the most basic principles of a theory in a convenient way. We could say we like Maxwell’s equations and the structure of benzene because they’re easy to draw and write in our lab notebooks. The French aviator Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote that, “A designer knows he has achieved perfection not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” Or maybe the value of brevity is less about the object, but, more extrinsically, about the ways which we can extend simple principles into different unique, complicated situations. We could say we delight at the beauty of how the four bases of DNA give rise to all the biological phenomena we observe. Whatever relation these two forms of brevity have with one another, we create a definition of conciseness that guides, not only aesthetic wonder, but also the rational justification of science itself. For example, Occam’s Razor is a well-known justification for using arguments and methods of reasoning that rely on fewer assumptions. From a purely philosophical point-of-view, it might not be so clear why one would favor theories that require less lines of code or equations that contain fewer variables. But, from statistical arguments of probability and randomness, it’s much more reliable for science to embrace theories and knowledge that minimize chances to be wrong. Fewer assumptions means smaller chances and lesser room for error, and, therefore, more precision and information.

# Python 3: Fibonacci series up to n

>>> def fib(n):

>>> a, b = 0, 1

>>> while a < n:

>>> print(a, end=' ')

>>> a, b = b, a+b

>>> print()

>>> fib(1000)

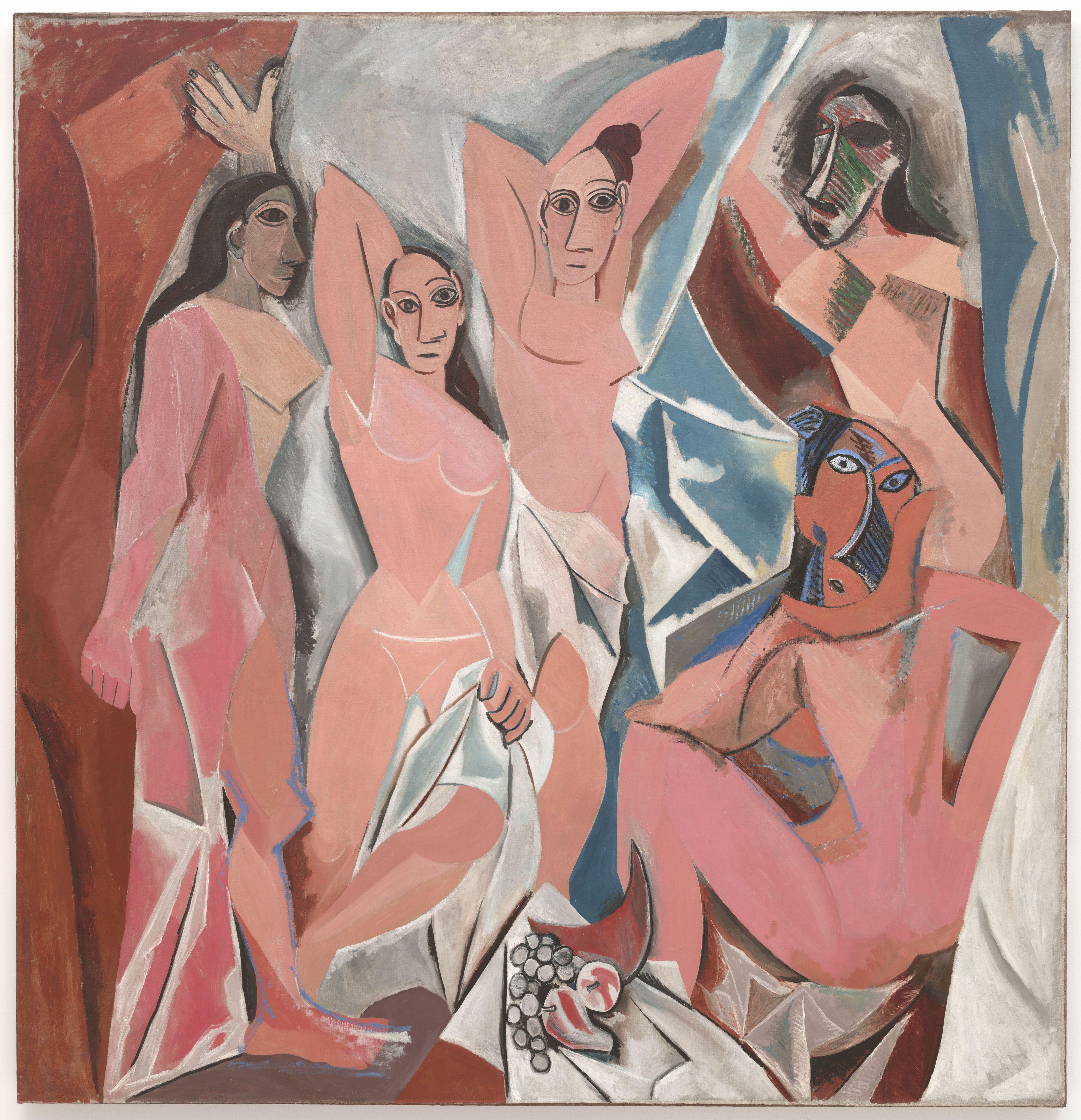

0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34 55 89 144 233 377 610 987The short, lines of code in Python show simplicity and elegance.Did the rise in scientific innovation over the 20th century coincide with the search for scientific elegance? And, if so, perhaps the modernist movements in art paralleled the ignition of our desire to discover elegance in science. The elegance in science comes form our ability to communicate information in the most succinct, concise way possible. Similarly, modernist imagery is known for being pure, rhythmic like the natural geometry of “microscope slides: straight-on views of textured systems (rather than objects in landscapes or architectural spaces)”. Modernist art also embraces the “form follows function.” Elegance as a modernist ideology that we desire to consume and interpret as much information as possible at any given moment. By emphasizing scientific and mathematical elegance as a maximization of utility, one would be reluctant to attribute the same scientific wonder and beauty to something subjective such as a sympathy-based philosophy. Instead, it would be more ideal to attribute the wonder and beauty we observe as results of how well art and science achieve its purpose, namely, through the maximization of this communication utility. This functionality of elegance in science may be an element of modernism.

“Wainwright Building” by Louis Sullivan has the “form follows function” principle in its design. Moreover, if beauty is in the eye of the beholder, are we adding a subjective human experience to science, a method of inquiry that must remain free from personal bias? Are we just deluding ourselves and inhibiting scientific progress by seeking knowledge for our own sense of beauty?

Perhaps we should embrace efforts to find wonder in science through elegance are best used for the betterment of science, but we should keep in mind the beautiful, artistic value that makes us human. Whether or not we champion nature or the dazzle of science overrules ourselves is important to the way we approach philosophical, legal, and ethical issues in science, medicine, and other fields of amazing work. It’s best for us to see science as, not just a way of obtaining information about the world, but also an art, a philosophy, and a beautiful journey into the unknown.

-

Imposter Syndrome: Noble Humility or Shameful Insecurity?

Read this article in the Indiana Daily Student here….From the first day of an introductory course in philosophy, psychology, or any field, we are inundated by the daunting knowledge and opportunities of the world. You realize that there’s so much to explore and learn. The things you know about the world might be wrong, and the things that you’re proud of might seem trivial, irrelevant, or unimportant in the face of the amazing things that others have done. Others might tell you that you’re intelligent, hardworking, or diligent, but you feel as though you’re not what everyone thinks you are. To make matters worse, socioeconomic and biological factors of the world might cause us to lose sight of what we truly have control over. We might think that we are only doing well because we were born to the right family, the top school, or the best genes. Students of color might feel as though they are recipients of affirmative action. Women might feel as though society should not expect them to believe they are intelligent. It doesn’t matter if you’re the prince or the pauper, the smartest or the strongest, the highest or the lowest. You wonder, “How did I get here?”

We may manifest our negative feelings in healthier ways. This might come about through modesty. But, too often, we have tendencies to deny any positive quality others say of ourselves. We may end up disliking moments in which we must show off or speak about our own accomplishments. This could be during communication such as presentations, interviews, meetings, or even personal ways such as completing coursework. During these times when we must actualize what we have done, you may pretend to be more skilled than you believe you are, or “fake it till you make it.” This will help you understand how to feel good about your accomplishments, since how you feel about yourself is only a feeling that should not reflect anything negative that you have done. And, while it is definitely noble to behave modest in our successes (be them intellectual or otherwise), it certainly doesn’t mean that we should ignore any positive trait we may have.As for factors that are truly outside our control (such as how we were born, what environment we grew up in), it is possible to take pride in what you have achieved while remaining grateful in one way or another. But, more importantly, it’s irrelevant to worry about whether or not factors outside your control have shaped your success. For the African American worrying that he/she might have had extra support in the college admissions process on account of his/her skin color or for the endowed wealthy student realizing that his/her family had access to the best resources, those are things that should not affect how you view yourself. But the position you are on the path doesn’t determine how successful you are. What you give to the world does. Maybe it’s not about the cards that are given to you, but the way you play them. That’s who you are who you are. You can make something meaningful of your life while simultaneously appreciating what others have given to you. And, at the end of the day, we don’t really know how lucky we could have ever been. So we should always remain grateful. That’s the type of modesty and appreciation that should promote humanism and virtues in the sciences (and the rest of academia).

-

"We are What We Do": The American Dream and Education

Who are we? At the beginning of many of my classes and activities (from kindergarten to college), my teachers sometimes coerce us to introducing ourselves to others. It usually involves telling others your name and a something you do. You can share that you play a sport, an instrument, or a video game; you can tell others about a hobby or a skill; or you can introduce yourself with your job. We see each other as trumpeters, origami enthusiasts, or accountants. We define ourselves by what we do. Why?Identity is, of course, not limited to the things that we do. We know who we are by what we look like, personal qualities and traits, memories, and stories. If someone shows you a picture of yourself, you can easily identify it as yourself. If someone asks you about what you did last summer, you can easily recall memories in order to identify the ones that you had done. But could you use impulses of motor control to identify the way you sign your name or throw a dart? We’ve always assumed that the things we do are implicitly contained within our knowledge, and, therefore, constitute who we are. The common link between perception and action has recently been explored very well through cognitive studies. Doing things might just be another part of identity this same way. Though the cognitive studies may serve a foundation for how this phenomena arises, we can explore norms and trends in history to fully understand how we are shaped by what we do.

The criteria and standards for collegiate admission might have influenced us into the norm of action as identity. As the mother prepares her three-year-old daughter for swimming lessons while picking up her middle-school son from science camp, people who dream of success know they need to do things. Academia’s use of extracurriculars as criteria have caused us to identify with those activities more. And our tremendous amount of effort we put into these sports, instruments, or any other activity makes us hold onto those extracurriculars. Regardless of our purpose, the self-identification with the activity may serve as some sort of reward (i.e., I want to call myself a “scientist” in some sense as a result of my scientific research). As a result, we wear our extracurriculars like badges. We introduce ourselves as “Hi I’m so-and-so and I play the violin!” We can achieve this “identification” when we do the things that we do. And we are pressured into activity with the fear that we don’t want to show up to work on Monday to share that you spent your weekend pondering life introspectively instead of doing something.

Land of Opportunity To Do What you Want

Taking pride in what we do might appeal to standards of free will and determinism created by American self-determination. Placing the identity in terms of what we do lends our identity to our own free will while yielding to the determinism of the activity itself. What I mean is that we choose what we do but the activity that we choose still has some predetermined value and meaning. When I tell people I’m a physics major, it appeals to the hard work I’ve put into my undergraduate career while simultaneously appealing to what we collectively, commonly associate with someone who studies physics (i.e., I’m an introverted lunatic who loves mathematics/science etc). Making action part of the identity gives us this power over who we are while conceding some of that influence to what is already established by the activity itself.

Who can deny that, as part of the American Dream, we want everyone to earn the rewards of what they do. We are promised that, as long as we work hard, there’s a chance. We all understand that it’s not possible for everyone to be rich, but it doesn’t stop us from the meritocratic understanding that we are here for the possibility. And, even as big cars and fancy houses are not always achievable, we still hold onto the credo that the hard work and determination will lead to success. These ideals lay the foundation for the beliefs that what makes us who we are is what we do.

College students are certainly no exception to the American Dream’s effects of identity with action. We spend our entire lives building ourselves up with experience as though we instantly become better people because we can simultaneously play a sport, learn a language, volunteer at a local shelter, and do well on tests. As such, we celebrate our value and identity as students as though they were determined by the things we do. We might see the things we do as value in and of themselves rather than as means to obtain the greater value within them. While it is true that one may benefit from taking part in those opportunities, it’s questionable whether or not they should be end goals in and of themselves and whether or not the value is intrinsic or extrinsic. Is this the American dream? Or have we lost sight of the purpose of the college education?

Why did I make this blog? Though my friends love creating profiles for themselves on LinkedIn, Twitter, or any similar social networking site, I preferred to abstain from succumbing my identity to the standards and stringent formats of established profiles. I wanted something that offered more freedom for me to create my own ideas, thoughts, and identity. By creating my own identity from my actions (as opposed to the discussed “action is part of identity”), I like to think it gives me more power in communicating to others. And maybe I can call myself a writer, too.

-

“We are What We Do”: The American Dream and Education

Who are we? At the beginning of many of my classes and activities (from kindergarten to college), my teachers sometimes coerce us to introducing ourselves to others. It usually involves telling others your name and a something you do. You can share that you play a sport, an instrument, or a video game; you can tell others about a hobby or a skill; or you can introduce yourself with your job. We see each other as trumpeters, origami enthusiasts, or accountants. We define ourselves by what we do. Why?Identity is, of course, not limited to the things that we do. We know who we are by what we look like, personal qualities and traits, memories, and stories. If someone shows you a picture of yourself, you can easily identify it as yourself. If someone asks you about what you did last summer, you can easily recall memories in order to identify the ones that you had done. But could you use impulses of motor control to identify the way you sign your name or throw a dart? We’ve always assumed that the things we do are implicitly contained within our knowledge, and, therefore, constitute who we are. The common link between perception and action has recently been explored very well through cognitive studies. Doing things might just be another part of identity this same way. Though the cognitive studies may serve a foundation for how this phenomena arises, we can explore norms and trends in history to fully understand how we are shaped by what we do.

The criteria and standards for collegiate admission might have influenced us into the norm of action as identity. As the mother prepares her three-year-old daughter for swimming lessons while picking up her middle-school son from science camp, people who dream of success know they need to do things. Academia’s use of extracurriculars as criteria have caused us to identify with those activities more. And our tremendous amount of effort we put into these sports, instruments, or any other activity makes us hold onto those extracurriculars. Regardless of our purpose, the self-identification with the activity may serve as some sort of reward (i.e., I want to call myself a “scientist” in some sense as a result of my scientific research). As a result, we wear our extracurriculars like badges. We introduce ourselves as “Hi I’m so-and-so and I play the violin!” We can achieve this “identification” when we do the things that we do. And we are pressured into activity with the fear that we don’t want to show up to work on Monday to share that you spent your weekend pondering life introspectively instead of doing something.

Land of Opportunity To Do What you Want

Taking pride in what we do might appeal to standards of free will and determinism created by American self-determination. Placing the identity in terms of what we do lends our identity to our own free will while yielding to the determinism of the activity itself. What I mean is that we choose what we do but the activity that we choose still has some predetermined value and meaning. When I tell people I’m a physics major, it appeals to the hard work I’ve put into my undergraduate career while simultaneously appealing to what we collectively, commonly associate with someone who studies physics (i.e., I’m an introverted lunatic who loves mathematics/science etc). Making action part of the identity gives us this power over who we are while conceding some of that influence to what is already established by the activity itself.

Who can deny that, as part of the American Dream, we want everyone to earn the rewards of what they do. We are promised that, as long as we work hard, there’s a chance. We all understand that it’s not possible for everyone to be rich, but it doesn’t stop us from the meritocratic understanding that we are here for the possibility. And, even as big cars and fancy houses are not always achievable, we still hold onto the credo that the hard work and determination will lead to success. These ideals lay the foundation for the beliefs that what makes us who we are is what we do.

College students are certainly no exception to the American Dream’s effects of identity with action. We spend our entire lives building ourselves up with experience as though we instantly become better people because we can simultaneously play a sport, learn a language, volunteer at a local shelter, and do well on tests. As such, we celebrate our value and identity as students as though they were determined by the things we do. We might see the things we do as value in and of themselves rather than as means to obtain the greater value within them. While it is true that one may benefit from taking part in those opportunities, it’s questionable whether or not they should be end goals in and of themselves and whether or not the value is intrinsic or extrinsic. Is this the American dream? Or have we lost sight of the purpose of the college education?

Why did I make this blog? Though my friends love creating profiles for themselves on LinkedIn, Twitter, or any similar social networking site, I preferred to abstain from succumbing my identity to the standards and stringent formats of established profiles. I wanted something that offered more freedom for me to create my own ideas, thoughts, and identity. By creating my own identity from my actions (as opposed to the discussed “action is part of identity”), I like to think it gives me more power in communicating to others. And maybe I can call myself a writer, too.

-

Factually Accurate about Factoids

Did you know that Stephen Hawking thinks IQ-swagger is for “losers”? Or that your friends have more friends than you do?What’s the difference between a rhetorical question and an attention-grabber? We often use a phrase like “Did you know” or something similar (such as “Today I learned”). These cliches, while purely rhetorical and lacking any actual inquiry of whether or not you knew a certain fact, implicitly challenging you to be able to assess your own knowledge and understanding of what you already know. And, by presupposing a factoid with the rhetorical “Did you know?”, we are insinuating that there is something unique and counterintuitive about the factoid. A “fun fact” is, of course, fun, but, like all other forms of discourse, it might have unfortunate implications about the way we perceive the world. For example, the fact that Elvis Presley failed music class reminds us of our lightheartedly unexpected ideals that academic performance doesn’t always translate to success and that “life sucks, but we all move on.” But the unexpectedness of the “fun fact” that there are people in Iran who mourn the victims of 9/11 might say something else. While it definitely is helpful for us to realize that the Iranian people (like most other people) are normal human beings, finding something “unexpected” or “surprising” about this factoid might show an underlying preconceived notion.

By posing a challenge to our current knowledge and understanding of the world (while accompanied by a fact that is pleasing), we are so entertained by trivial curiosity. This explains why so many “clickbait” places on the web imply that there are things we “should know” or that “will surprise us!” In fact, in the 1970’s, the word “factoid” was originally coined as “facts which have no existence before appearing in a magazine or newspaper.” For this reason, we can look at the information carried by factoids as evidence of underlying assumptions (such as my example with Iranian mourners) among common folk and everyday thinkers, as opposed to rational reason-based heavyweight information of academia and knowledge. Perhaps our obsession with factoids and trivia over past few decades give us comfort that things can still be “simple” in the confusing world of ever-increasing knowledge and uncertainty. And, since this psuedoknowledge is grounded in unexplored depths of mainstream mass media, we end up with misconceptions and misleading ideas such as “in the Peruvian language there are 1,000 words for potato.” In addition, this shows that, in our everyday language, we have a way of speaking that helps us understand how much we truly understand what we know. Who would have thought that such epistemic virtue could be derived from something as simple as a Snapple fact?” I bet you didn’t know that!

-

Re-imagining the Self and Freedom from Distraction

Last Thursday, I visited the Ryerson and Burnham Library of the Art Institute of Chicago where I meandered the solitude granted by the bookshelves of cultural theory. Away from the hustle and bustle of crowded exhibits, I sat against a wall with a book on American History sitting in my lap. I savored the academic freedom of choosing what to study from a myriad of books and the personal freedom granted being far from the nature of the city and research lab. But, in the most fundamental sense, what is freedom? I personally greatly enjoy the freedom given to me by virtue of working in a dry lab. Since I perform my entire scientific research on a computer, I am not burdened by the physical limitations of experimental science, and there exist swaths of knowledge only a few keystrokes away. Does having more options and opportunities give us more freedom? Is freedom something that we should strive to achieve at all costs?

I would love to read some of Matthew Crawford’s new book, The World Beyond Your Head, if I didn’t have six other tabs open at the current moment (RescueTime only works to save my sanity so much). Crawford, a fierce critic of distraction culture, draws from philosophical rhetoric of Locke and Descartes to describe the way we, human beings, approach the idea of freedom. I am comforted by Crawford’s argument that technology only has a small responsibility of the reason why we are so enthralled by distraction. As I struggle to find a solace in the bombardment and conformity of information and ideas that prevail through today’s culture, Crawford’s wisdom helps me understand what we, human beings, truly find important from a humanistic point-of-view. Though his arguments are too complicated to be completely explained in the medium of a blog post, one might be interested in learning how the anxiety and worry that our individual autonomy needs to be saved from the clutches of authoritarian tyranny fails to appreciate the individual. Inspired by the advertisements that clutter our urban setting, Crawford chooses to explain social phenomena with heavy, fundamental philosophy.

When he’s not spending his spare time building motorcycles, Crawford explores from gamblers to chefs as he deconstructs the human self from our modern tendencies. Even though it the tendencies and currents of contemporary culture are often too complex and strife with external influences to be analyzed philosophically, Crawford’s reasoning backs up the description of our current society very appropriately. With a BS in physics and a PhD in philosophy, Crawford is one of the few researchers so strong-willed to put a question mark at the end of the most basic assumptions about freedom and opportunity that have been firmly ingrained into the Western mind. We can blame the Enlightenment for our notion that “more opportunities” implies “more freedom.” But should we throw away any idea of Kantian thought in our current work environment? Not so. According to Crawford, even the most elemental workers (such as welders and construction workers) can find a true sense of individuality under the authorities of society. Similarly, my desire to be free, that could possibly be granted by the isolation of a library in an Art Institute, might only be caused by my perceived regulations and limitations by higher-ups.

The modern discourse of the intersection of philosophy and science is strife with controversy and strong opinions, but one famous physicist had some interesting thoughts on individual freedom or, rather, free will. In Einstein’s interpretation of Schopenhauer, he writes:

My Credo[Part I]“I do not believe in free will. Schopenhauer’s words: ‘Man can do what he wants, but he cannot will what he wills,’ accompany me in all situations throughout my life and reconcile me with the actions of others, even if they are rather painful to me. This awareness of the lack of free will keeps me from taking myself and my fellow men too seriously as acting and deciding individuals, and from losing my temper.”

(Schopenhauer’s clearer, actual words were: “You can do what you will, but in any given moment of your life you can will only one definite thing and absolutely nothing other than that one thing.” [Du kannst tun was du willst: aber du kannst in jedem gegebenen Augenblick deines Lebens nur ein Bestimmtes wollen und schlechterdings nichts anderes als dieses eine.])

And, in light of this, Einstein formulated his famous discoveries on, well, light. Despite the enticing appeal of a physicist speaking about philosophical ideas that would create the setting for his greatest discovery, we must not be quick to jump to conclusions that questions about free will and human nature can ever be explained by science. However, those people who truly examine the way we approach science and philosophy have an important word on the rest of society. In tune with the philosophical undercurrents of society, Einstein’s reflections on the political events of the mid-20th century would later guide the movements for peace and humanism that, too, result from a relentless desire to be free. Under Einstein’s strong influences on social justice and disdain for the extravagance, we entered an age of insecurity and uncertainty about the future. And, as I lean back in my chair and sip coffee while running genetic analysis software in the comfort of my dry lab, maybe I should be grateful for not being able to do a thing.