Tag: Philosophy

-

IU professor unifies science and philosophy to study disease

-

Aristotle’s crafty advice on skills in the workplace – and everywhere else in life

“For it is owing to their wonder that men both now begin and at first began to philosophize.” – Aristotle (Metaphysics, Part II) When someone needs to play the flute, it should be the best flute-player. Aristotle’s craft analogy helps us understand our virtues much like how we achieve skills, be them for the workplace or for life. The Greek philosopher probably didn’t know much about social media or TED Talks. But there’s a thing or two he can teach about these skills.

We like to talk about skills. We emphasize workforce skills such as communication and presentation. Much of the liberal arts education prizes skills as rewards for students. This could be verbal skills by studying history or deductive skills through mathematics. And more vocational training might include specific technical skills. And, in other places, there are life skills – empathy, decision-making, or whatever you want to learn. Every walk of life seems to be a skill – a way to improve ourselves.

These skills we gain through practice, be it learning from bad decisions or straight out of intuition, are like to the way we become better people. We treat life as though our skills are a game – a craft. Over time gaining more experience honing our skills. Like an athlete at a training ground or a writer on a blog, everything is an opportunity to learn.

Aristotle might know a thing or two about learning to better ourselves – including bettering our morals. In his work “Nichomachean Ethics”, he explained that one must get all virtues in due proportion with one another. This was to pursue the chief good, Eudaemonia.

Eudaemonia is a sort of practical wisdom. It’s how we hold our virtues and goods in due proportion with one another. As we experience life, we learn the appropriate methods, conditions, and amounts of virtues. There’s a right and wrong time to be courageous, an appropriate amount of compassion to be had, and various ways to be patient. The philosopher explained that this sort of practice with virtues is much like learning a craft, such as playing a violin or building a boat. If we use analyze these crafts in the similar vein of skills, the way we practice skills may help us understand how we become better human beings.

A very unique set of skills. Aristotle’s craft analogy has two parts. First, virtue and crafts alike in that one learns both of them through practicing or doing them. We learn how to be courageous through acting the way a courageous person would act, and one learns how to make a violin through the act of making a violin. When someone acts the way a courageous person would act, then he or she establishes rules or criteria under which one should be courageous. The person might exercise a specific amount of courage in certain situations, and, in other situations, not show courage at all. By an appropriate exercising virtues, we get a practical understanding of them.

Through this, we master the virtue and learn how to be courageous. And, to learn how to make a violin, one must practice the act of violin-making.

The second part is that mastering the virtue or craft requires an understanding of why that action is the right one to perform. When a courageous person is courageous, he or she must understand the ways in which that courageous act is the right one to perform. The courageous act has its value of being the courageous act intrinsically. But, in these reflective dimensions of virtue, the courageous person must understand why that act is virtuous.

The act may be a courageous act because it is under a certain reason, such as choosing to take a stand against racism in a racist society. The agent may weigh attitudes of others in their perception of the agent as a courageous person. Or the agent may judge him/herself as courageous. The person doesn’t have to know the exact role of virtues in the most intricate, detailed sense to be a virtuous person. And the knowledge of the virtues itself doesn’t make one a virtuous person.

Rather, the person becomes virtuous by exercising virtues appropriately. When one performs an action when making a violin, he or she must understand how that action is correct or necessary for making a violin. There might be a certain tightness of the string necessary or there might be a specific type of wood that produces the unique sound. Those are reasons why certain actions are necessary for violin-making, just as there are reasons a virtuous act is virtuous.

The analogy is not without limitations. It might seem as though virtues are exactly like crafts. But Aristotle recognized that the craft analogy does not hold in every way. The craft-maker’s can complete individual tasks while the virtuous person’s virtues are never “completed.” The process of making a violin ends when one stops making a violin, but he or she is still a violin-maker. But when a virtuous person stops acting courageously, the act is over. The individual is no longer courageous. Hence, that person is no longer a virtuous person). To maintain the status of being a craft-maker, one doesn’t have to constantly perform the craft. But to maintain a certain virtue, one must keep performing that virtuous act in the ways that are appropriate.

Joseph de Ribera The actions of making are craft are only instrumental toward the end goal of completing the craft. Virtues are not only instrumental to achieving eudaemonia, but have intrinsic value as well. When one carves wood to make a violin, one does so as a means to have the appropriate wood. When one is courageous, it’s instrumental to bring about the end of achieving a chief good. But there it is also worthy to pursue that act in itself.

These similarities and differences give us a more precise view on the skills in life. We want to learn skills, professional or not, the same way we want to become good human beings. This analysis of how those professional skills, like communication, decision-making, or problem-solving, with the way we understand virtues or crafts can help us become better workers, too.

Speaking of crafts, Google’s aptly-named Project Aristotle studied optimal working conditions. It found that an individual’s ability to take risk without fear of judgement from peers was the most important condition for success. We might interpret this as a virtue of courage, tenacity, confidence, or something else. If we look at it, Google might enjoy an Aristotelean analysis of the nuances of the skill.

We need to turn back to Aristotle to understand our skill-centered rhetoric. We need a sharper, less ambiguous distinction between our own morals and our skills. These similarities and limitations can give a framework for what sort of skills we need in life – and how to meet them. Only then will we attain Eudaemonia.

-

Mental fatigue takes its toll on the soul

“As an ambitious executive, it’s important that you believe that you will deserve credit for everything you achieve. As a human being, it’s important for you to know that’s nonsense.” – David Brooks Burnout sucks. It’s easy to tell yourself you just need to work fewer hours or take more days off, but sometimes there’s a consistent loss of value in what you’re doing when you feel exhausted. Letting go might shake your understanding of reality.

Alloy, L., & Abramson, L. (1979). Judgment of contingency in depressed and nondepressed students: Sadder but wiser? Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 108 (4), 441-485 DOI: 10.1037/0096-3445.108.4.441In high school, my track and field coach used to tell us, “If you’re sore, you’re not trying hard enough, and, if you’re not sore, you need to try harder.” It’s hard to deny that, in our meritocratic individualistic society, our work is our religion. It’s our measure of self-worth and success in the world. We tell ourselves to push ourselves to our limits, until we drop to our knees. For those of us who become exhausted from our work, this sort of tiredness can be flattering. Who wouldn’t want to tell themselves that they’re just working “too hard for themselves”? Working even harder might mean getting only enough sleep necessary to function, opting for a sandwich instead of a relaxing hour-lunch, or shaving while you’re in your car. But, aside from the physical demands of life, the burned out soul perceives his/her world differently. And this could lead to mental health issues.

Someone suffering from depression might feel their exhaustion as a symptom of weirdness. They just don’t fit in with society’s standards so they struggle with unique psychological pressures. The romanticized ideal of exhaustion comforts the depressed individual as a misunderstood genius or a drummer with a different beat. And, with this mental fatigue, their efforts may be a fragile, fruitless pursuit.

We come to question our own worth. We give ourselves excuses like we’ve been brought to where we are by sheer luck, opportunity, or some magical force that swayed us to where we are. We can barely find ourselves with much to say about ourselves when we constantly find out more and more about the world.In one extreme, imposter syndrome causes individuals to devalue their own efforts while, in the other, the Dunning-Krueger effect causes people to overestimate their own abilities. Under more commonplace circumstances, many underestimate luck when things go well for them while blaming poor results on external mishaps. This interpretation of randomness, though, makes decision-making difficult and causes us to forget about who we really are. Even for people who don’t value their own worth as much as they should, this sort of luck is better seen as something that affects everyone and the universe altogether, rather than simply a force that pushes and pulls on an individual’s efforts to success. If people can remember that hard work plays a significant role in success while still acknowledging the amazing fortunes that have brought them to where they are, they may kindle that fighting spirit that keeps them going.

As Professor of Economics Robert H. Frank explains, people who recognize the value of good fortune in their lives:

“are much more likely than others to contribute to their community and to support the kinds of public investments that created and maintained the environments that made their own success possible. They’re also substantially happier than others, and their gratitude itself appears to steer additional material prosperity their way.”

Psychologists L. B. Alloy and L. Y. Abramson showed self-assessments of depressed students were more accurate and realistic than the self-assessments of others. Their hypothesis remains controversial: not only does it lack a general consensus among the scientific community, but it raises thorny ethical questions about depression. While it’s commonsense that mental illness is more than just a physiological response, the extent to which a bodily response should account for humanistic traits of responsibility and autonomy are up for debate. And understanding the depressed mind, overwhelmed and unconfident, might partly explain how we’ve come to value exhaustion.

With this sort of depressive realism, those who are depressed might understand the world more accurately than other people. They can more readily understand how much of their life is due to their own efforts and how much is due to the hand of the universe. And, as a result of this misunderstanding between themselves and the rest of the world, they struggle.This isn’t to say we should value depression as a badge of honor, virtuous symbol, or goal to attain. Instead, it’s more about being more realistic about why and how we feel the way that we do.

This interpretation has its drawbacks, though. Contrary to the hypothesis by Alloy and Abramson, we commonly view depressed people as having a negative view on reality, not a more realistic one. They may be less willing to value their own efforts, and more likely to blame things as the result of fortune. And all human beings, depressed or not, have their biases in their interpretations of the world.

How do we understand our own exhaustion? Turning to literature is always there. Dr. Lydgate from Dante’s “Divine Comedy” loses sight of his ideals while Jay Gatsby of Fitzgerald’s novel supposedly represents the darker side of the American Dream. Individual accounts of mental illness, such as blogs and social media forums, give a personalized lens of how tiring life can be. The meticulous, slow-and-steady pace of psychotherapy may help us find us find our “pool of tranquility,” as psychoanalyst Josh Cohen puts it. These methods can help us make sense of things, but understanding the roles that luck, fortune, handwork, or whatever it is that has brought you to where you are in life can help you make sense of your exhaustion, be it due to an existential crisis or a few long shifts at work.

We’ll be grateful for everything else in life, too.

-

Nostalgia, networks, and nuance of Pokémon Go

Trying to stay awake It feels like 1999 again. Aside from the email scandals against Hillary Clinton, the reboots of childhood franchises, and the bright colors of this website, the déjà vu makes everything feel all too familiar. And the wildly successful mobile app Pokémon Go rages on. Reminiscent of the days of trying to catch ’em all when we were younger, it’s less about finding the elusive Mewtwo and more about finding ourselves.

Much has been written already on Pokémon Go as the next big thing. In the video game and media franchise, players test their skills to find and capture creatures known as Pokémon. But what makes the franchise amazing is how well the Pokémon themselves are designed. Each Pokémon has their own unique abilities. They have personalities and character. Charizard is a boastful, hotheaded dragon. Clefairy is a cute, friendly cuddly bear. And, as you train your Pokémon, they grow stronger. Some can evolve into (although it is more akin to metamorphosis rather than evolution) even more powerful Pokémon.

Back in the 90’s the Pokémon fad took over the nation by storm. Teenagers in my neighborhood were linking their Gameboy Colors to battle with their Gengar and Nidoking. I was sneakily trading my Geodude trading card with other students in my kindergarten class. My parents took me to see the movie at the local theatre. Unlike other shows and media, Pokémon set itself apart in the way it balanced the individual characteristics of a Pokémon with a larger sense of belonging. They formed networks in this sort of connectedness. Each Pokémon has a unique set of attacks, design, and strength, but some share the same type, lineage, or other relations to one another. Ekans, the snake Pokémon, routinely eats the eggs of Pidgey, a pigeon creature. They can play into each other’s strengths and weaknesses, such as the fire lizard Charmander’s advantage over a grass plant like Bulbasaur. This balance also shows in the way Pokémon relate to our real world. Koffing and Muk are, respectively, a sphere of nauseous gas and a puddle of slime. They reference our planet’s troubles with pollution. Farfetch’d, a duck wielding a leek, alludes to a popular Japanese saying.

This means children and adults can identify with Pokémon much more easily than they would, say, identify with the protagonist of a romance novel or a superhero movie. These balances and relationships give rise to complexity that we see in ourselves. Some of us have angry days when we rage like a Gyarados. Other times we can admire the beauty and serenity of Lapras. Pokémon themselves become much more than individual fighting pawns, but characters with the depth and substance that most video game characters struggle to achieve. And, with these established relations in place, we can keep tabs on whatever new Pokémon we come across. Even the names of Pokémon themselves borrow from Japanese and Western roots with a creative voice in each of them (e.g., “Squirtle” as a play on “squirt” and “turtle.)

And, above else, Pokémon feeds our imagination of learning and exploring the world. The same way philosophers seek to analyze fundamental questions and biologists classify all species and organisms, a Pokémon trainer seeks to catch ’em all.

Though there is much potential in this sort of analysis, the daily trials of Pokémon Go might not be any of that. Our co-workers and significant others might be spend their time staring at their phones just because it’s fun and addicting. But, aside from the momentary satisfaction, the culture which we currently inhabit might help us see the entire phenomenon as a nostalgia trip to our playground days, except, instead of dial-up cyberspace we use social media. Instead of fearing AIDS and homosexuality, we fear terrorists and financial instability. Instead of tying our jackets around our waists, we tie our hair in man buns.

And Zubat still won’t leave me alone in dark places Our country is experiencing a cultural shift in our individual sense of belonging. We’ve brought our own individual identities, race, sex, class, and everything else under scrutiny. We’re upset with elites and the establishment’s exercise of power. Our politics have become more about personal grievances and less about overarching policy. Rising sensitivity and suspicion have made us more partisan and fueled by animus outrage.

And maybe Pokémon Go hearkens back to the older days. The 90’s participatory culture of radio and cable TV is now ever-alert, yet detached smartphone trendiness. The previous generation’s rejections of grand narratives and categorization have manifested in today’s myopic, schizophrenic political discourse. The messiness that is our country’s conversations on controversial issues of race and gender that we’ve sought to erase has lingered with us today, and, in some ways, worsened tensions between races and other types of groups. And the retro gaming that has re-manifested itself in a smartphone app is another reminder.

Joseph Tobin, Professor of Education at the University of Georgia, studied the rise of Pokémon in the 90’s. On the way people found different pleasures in Pokémon, he commented:

Drawing on a concept of Michel de Certeau (1984), who makes a distinction between the strategies of the powerful (colonizing governments, invading armies, bosses) and the tactics of the weak (colonial subjects, resistance fighters, employees), we can see children as tacticians who use the means at hand to extract pleasure where and when they can find it.

de Certeau’s examination of the producers and consumers isn’t entirely about a streamlined popular culture nor is its primary focus some sort of struggle against power. He looks at the way people walk from place to place. Drawing influence from Wittgenstein’s philosophy of ordinary language, de Certeau explains how our everyday actions are restricted by what is given by the powerful. By navigating between buildings and down roads, individual people choose their paths that have been established by the city architects. The producers of the city employ strategies for official purposes. The consumers of the city folk use tactics with limitation, yet still ultimately dictated by the powerful.

We can keep it in mind on our everyday walks with Pokémon Go.

The same way some of us play Pokémon for self-identification while others play the game to meticulously catch ’em all, we seek our own agency. We use our own tactics in the context of the strategies given by those in power. It puts the individual with the ability to choose and connects us with others. The connectedness of Pokémon only remind us of everything we desired. The balance between individualistic self-expression and a larger, more universal belonging parallel the world of Pokémon. These are the tactics we cling to.

-

Ethics in cruise control: self-driving dilemmas

“Nietzsche, take the wheel.” Self-driving cars may take us wherever we want to go, but they won’t know where unless we tell them. And with the first death of a man riding autopilot in a self-driving car, we find ourselves with the same old questions we’ve always had. What should an autonomous car do when human life is at stake?

The ethical dilemma of whether a car should swerve out of the way to kill one person in order to save others is a form of the trolley problem. Now, engineers, scientists, and policymakers ask the big questions philosophers have debated for centuries.

The question is driven by our ethical concerns for the general public. We make these decisions with regards to the effects they have on our society as a whole. Self-interest usually takes the backseat, and our idealistic utopias emerge. We’d love to live in a world in which a car can simply calculate the risks and benefits of various decisions to which action to take. And, in this sense, the decisions of self-driving cars aren’t too different from our current methods of engineering. When we make airbags, we design them so that they would save as many people as possible while taking into account the costs of manufacturing.

The experimental ethics approach of Jean-François Bonnefon, researcher at the Toulouse School of Economics, probes the big questions for answers. By surveying the public and designing experiments that take into account various situations of self-driving cars, we can get a general idea of how people view them. The researchers ask questions to the public about different scenarios and how they would want their cars to act. This includes the general situations of swerving out of the way of a crowd of people in order to hit one person, but also more variable specific cases, such picturing yourself in the self-driving car, as opposed to someone else. It would take those opinions of the public into account so that the designers of self-driving cars can program their cars with their thoughts in mind.

It seems reasonable and straightforward. Cars would perform the actions which result in the fewest deaths. But let’s not let the idealism of utilitarian motives get the best of us. The same study showed that, though people preferred cars to drive this way, they wouldn’t want to buy cars or be the drivers of them. No one wants to be the driver of the car that makes the decision to swerve and kill a single person in order to save the lives of a greater number of people. The findings illustrate the conclusion quite well. When people have an overall goal for the public in mind, that is, protecting the lives of as many people as possible, they agree it should be pursued. But every individual person doesn’t find it in their own self-interests to do it.

What this means is we need a greater social change in our understanding of ethics before we can put our own solutions into action. Some sort of a collective understanding of individual decisions being part of a bigger picture would lessen the burden on the single consumer in buying a self-driving car. The experimental ethics work should also encompass what the outcomes of those automatic driving decisions are.

Jean-François Bonnefon, Azim Shariff, & Iyad Rahwan (2015). The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles Science, 352(6293), 1573-1576 (2016) arXiv: 1510.03346v2

-

Who cares about the ill? The moral grounds of mental health

Philosophers like to argue about our values. We can’t simply stop at empathizing with different belief and conditions of other people. We must know where those values come from in order to address the thorny ethical dilemmas that plague our lives. Dr. Agnieszka Jaworska at UC Riverside delineates various forms of moral standing in which humans help each other. And, when it comes to mental health, this sort of moral standing understanding might be just what we need.

When we ask why we care about the people we value, the answer might appear obvious. If we value something, surely we care for it on account of that value. But caring is complicated. We often care about people out of social ties, and we care about our own selves in different ways. These grounds can be emotional, like our abilities to desire, or more reason-based, such as our abilities to determine what actions and behavior we can perform. We say we should save the live of a human being instead of, for example, the life of a chicken, on the human being’s ability to reason.

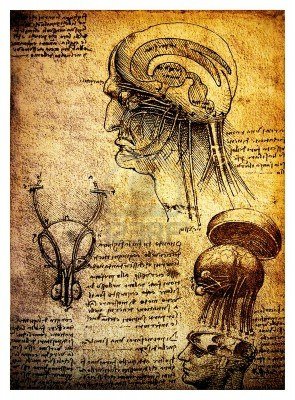

A grasp of our moral standing would aid in our treatment of the mentally ill. A patient with late Alzheimer’s disease might only find him/herself with bodily needs, such as food and water. Babies and even unborn children may be subject to speculation with responsibility, autonomy, integrity, and other factors depending on their physiological structures. And caring can cover the emotional aspects we normally associate with the action. As Jaworska explains, the internalities of caring on human behavior can’t be ignored. The way we care about things gives us desires and attitudes that we don’t simply experience for a moment or two, but absolutely “own” as part of ourselves. This act of owning an attitude gives rise to the capacities of caring. And Jaworska argues that our capacities for emotion are actually enough for our grounds for the cognitive and reflexive capacities of caring. Other opinions include those who follow Kant and claim that, instead of an emotional ground, the capacity for caring comes from a reason-baed ability to form decisions. From these capacities, we can talk about those who suffer from disease (especially with mental health issues) on the right page.

This means our understanding of medicine and medical education needs this moral grounding. More power to the fields of philosophy and the rest of the humanities.