Paul Feyerabend (1924-1994), having studied science at the University of Vienna, moved into philosophy for his doctoral thesis, made a name for himself both as an expositor and (later) as a critic of Karl Popper’s “critical rationalism”, and went on to become one of the twentieth century’s most famous philosophers of science. An imaginative maverick, he became a critic of philosophy of science itself, particularly of “rationalist” attempts to lay down or discover rules of scientific method.

|

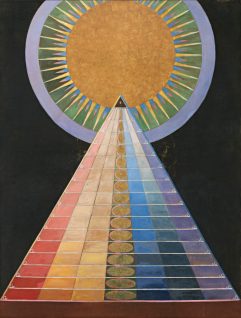

| Hilma af Klint, Group X, No. 1, Altarpiece, 1915 |

Born to the son of a civil servant and a seamstress, Feyerabend took up reading as well as singing during his childhood. Having passed his final high school exams in March 1942, he was drafted into the Arbeitsdienst (the work service introduced by the Nazis), and sent for basic training in Pirmasens, Germany. Feyerabend opted to stay in Germany to keep out of the way of the fighting, but subsequently asked to be sent to where the fighting was, having become bored with cleaning the barracks! He even considered joining the SS, for aesthetic reasons. His unit was then posted at Quelerne en Bas, near Brest, in Brittany. Still, the events of the war did not register. In November 1942, he returned home to Vienna, but left before Christmas to join the Wehrmacht’s Pioneer Corps. Their training took place in Krems, near Vienna. Feyerabend soon volunteered for officers’ school, not because of an urge for leadership, but out of a wish to survive, his intention being to use officers’ school as a way to avoid front-line fighting. The trainees were sent to Yugoslavia. In Vukovar, during July 1943, he learnt of his mother’s suicide, but was absolutely unmoved, and obviously shocked his fellow officers by displaying no feeling.

In 1945, Feyerabend was shot in the hand and in the belly during the retreat from the Russian Army. The bullet damaged his spinal nerves. Two years later, he’d return to Vienna to study history and sociology at the University until later transferring to physics. His first article, on the concept of illustration in modern physics, published. Feyerabend could be described as “a raving positivist” at the time. The student found himself persuaded him of the cogency of realism about the “external world” (Popper’s important arguments for realism came somewhat later). The considerations Hollitscher deployed were, first, that scientific research was conducted on the assumption of realism, and could not be otherwise conducted, and, second, that realism is fruitful and productive of scientific progress, whereas positivism was simply a commentary on scientific results, barren in itself.

Feyerabend received his doctorate in philosophy for his thesis on “basic statements” in 1951. He applied for a British Council scholarship to study under Wittgenstein at Cambridge, but Wittgenstein died before Feyerabend arrived in England, so Feyerabend chose Popper as his supervisor instead.

In 1975, Feyerabend published his first book, Against Method, setting out “epistemological anarchism”, whose main thesis was that there is no such thing as the scientific method. Great scientists are methodological opportunists who use any moves that come to hand, even if they thereby violate canons of empiricist methodology.

In his article, “How to Defend Society Against Science”, the philosopher sought to defend society and its inhabitants from all ideologies, science included. All ideologies must be seen in perspective. One must not take them too seriously. One must read them like fairytales which have lots of interesting things to say but which also contain wicked lies, or like ethical prescriptions which may be useful rules of thumb but which are deadly when followed to the letter.

Now, is this not a strange and ridiculous attitude? Science, surely, was always in the forefront of the fight against authoritarianism and superstition. It is to science that we owe our increased intellectual freedom vis-a-vis religious beliefs; it is to science that we owe the liberation of mankind from ancient and rigid forms of thought. Today these forms of thought are nothing but bad dreams-and this we learned from science. Science and enlightenment are one and the same thing-even the most radical critics of society believe this. Kropotkin wants to overthrow all traditional institutions and forms of belief, with the exception of science. Ibsen criticizes the most intimate ramifications of nineteenth-century bourgeois ideology, but he leaves science untouched. Levi-Strauss has made us realize that Western Thought is not the lonely peak of human achievement it was once believed to be, but he excludes science from his relativization of ideologies. Marx and Engels were convinced that science would aid the workers in their quest for mental and social liberation. Are all these people deceived? Are they all mistaken about the role of science? Are they all the victims of a chimaera?

To these questions my answer is a firm Yes and No.

Now, let me explain my answer.

The explanation consists of two parts, one more general, one more specific.

The general explanation is simple. Any ideology that breaks the hold a comprehensive system of thought has on the minds of men contributes to the liberation of man. Any ideology that makes man question inherited beliefs is an aid to enlightenment. A truth that reigns without checks and balances is a tyrant who must be overthrown, and any falsehood that can aid us in the over throw of this tyrant is to be welcomed. It follows that seventeenth- and eighteenth-century science indeed was an instrument of liberation and enlightenment. It does not follow that science is bound to remain such an instrument. There is nothing inherent in science or in any other ideology that makes it essentially liberating. Ideologies can deteriorate and become stupid religions. Look at Marxism. And that the science of today is very different from the science of 1650 is evident at the most superficial glance.

For example, consider the role science now plays in education. Scientific “facts”are taught at a very early age and in the very same manner in which religious “facts”were taught only a century ago. There is no attempt to waken the critical abilities of the pupil so that he may be able to see things in perspective. At the universities the situation is even worse, for indoctrination is here carried out in a much more systematic manner. Criticism is not entirely absent. Society, for example, and its institutions, are criticized most severely and often most unfairly and this already at the elementary school level. But science is excepted from the criticism. In society at large the judgement of the scientist is received with the same reverence as the judgement of bishops and cardinals was accepted not too long ago. The move towards “demythologization,” for example, is largely motivated by the wish to avoid any clash between Christianity and scientific ideas. If such a clash occurs, then science is certainly right and Christianity wrong. Pursue this investigation further and you will see that science has now become as oppressive as the ideologies it had once to fight. Do not be misled by the fact that today hardly anyone gets killed for joining a scientific heresy. This has nothing to do with science. It has something to do with the general quality of our civilization. Heretics in science are still made to suffer from the most severe sanctions this relatively tolerant civilization has to offer.

|

| Wolfgang Tillmans, Philharmonie Bloch III, 2017. |

Is this unfair? Have I not presented the matter in a very distorted light by using tendentious and distorting terminology? Must we not describe the situation in a very different way? I have said that science has become rigid, that it has ceased to be an instrument of change and liberation, without adding that it has found the truth, or a large part thereof. Considering this additional fact we realize, so the objection goes, that the rigidity of science is not due to human will. It lies in the nature of things. For once we have discovered the truth. What else can we do but follow it?

This trite reply is anything but original. It is used whenever an ideology wants to reinforce the faith of its followers. “Truth” is such a nicely neutral word. Nobody would deny that it is commendable to speak the truth and wicked to tell lies. Nobody would deny that_-and yet nobody knows what such an attitude amounts to. So it is easy to twist matters and to change allegiance to truth in one’s everyday affairs into allegiance to the Truth of an ideology which is nothing but the dogmatic defense of that ideology. And it is of course not true that we have to follow the truth. Human life is guided by many ideas. Truth is one of them. Freedom and mental independence are others. If Truth, as conceived by some ideologists, conflicts with freedom, then we have a choice. We may abandon freedom. But we may also abandon Truth. (Alternatively, we may adopt a more sophisticated idea of truth that no longer contradicts freedom; that was Hegel’s solution.) My criticism of modern science is that it inhibits freedom of thought. If the reason is that it has found the truth and now follows it, then I would say that there are better things than first finding, and then following such a monster.

Leave a comment