I’d like to proudly announce the creation of my new website “A history of artificial intelligence.” (http://ahistoryofai.com). Through it, I show the various ways artificial intelligence has changed since its dawn thousands of years ago. I hope to use this website to craft a story of understanding between different civilizations and eras citing writers like Mary Shelley and scientists like Claude Shannon. Stay tuned as I add more and educate the world with it.

Category: Blog

-

New website: "A history of artificial intelligence"

-

How to improve your moral reasoning in the digital age

Chinese scientists recently created gene edited babies using the controversial CRISPR-Cas9 technique. Scholars have alarmed the world about the ethical questions raised by genetic engineering. Writers also grappled with the recent explosion of machine learning and its effects. This includes the science behind how computers make decisions. This way they can determine its effects on society. These issues of artificial intelligence arise in self-driving cars and image recognition software. Both issues raise questions of how much power humans should exert in controlling genes or computers.

I believe we need to examine our heuristics and methods of moral reasoning in the digital age. With these issues of the information age, I’d like to create a generalized method of moral reasoning. With this, any human can address these issues while remaining faithful to the work of philosophers and historians.

In 1945 mathematician George Poyla introduced “heuristic” to describe rough methods of reasoning. It should come as no surprise that I fell in love with the term immediately. I drew fascination in how way we could make estimations and speculate on issues. In science in philosophy, we can discuss them in such a way to find solutions and benefit the world.I’ve written on the digital-biological analogue in these issues. Scientists and engineers harness the power of machine learning to form decisions from large amounts of data. Though this is data that we, humans, feed to computers, the decisions comes algorithm design and even aesthetic choices. The algorithm design would be the scientific process a computer performs in making decisions. An aesthetic choice might be the way an engineer designs the appearance of a computer itself. The results of these choices illustrate the tension brought upon by robots making these decisions. They arise in the way self-driving cars make decisions or what sort of rights might a robot have. The ways our sense of control and autonomy, the way we control our lives, come into play are common among genetic engineering and artificial intelligence. The ways our sense of control and autonomy, the way we control our lives, come into play are common in them. One of the basic principles of health care ethics and a subject to debate, autonomy pervades through everything.

We can reason about science by some notions of scientific realism, as philosophers argue. The philosophical notion of scientific realism generally holds that our scientific phenomena are real. The atoms that make up who we are or the genes of our DNA are phenomena that exist. One might argue for scientific realism because our scientific theories are the closest we can approximate of them. Through this line of thought, we should take positive faith in the world described by science. Under this interpretation, our arguments about digital-biological autonomy depend upon what sort of decisions empirical research dictates we can create. Our arguments about digital-biological autonomy may depend upon what decisions empirical research dictates. We can rely on science to show this. A constructed idea of an autonomous driver that algorithms dictate could make autonomous decisions. In her paper “Autonomous Patterns and Scientific Realism”, professor of philosophy Katherine Brading argues that scientific theories, under a notion of scientific realism, should allow for phenomena partially autonomous from data itself. It emerges about the context of the data. It comes down to creating an empirical process, from lines of code on a computer screen to the swerving motion a self-driving car. We can dictate what choices would be moral and immoral because those processes hold the truth of autonomy.

One might opt to take a more pessimistic view. It’s possible our scientific reasons for phenomena only amount to persuasion. A proponent of this point of view may argue that, we aren’t reasoning: we’re rationalizing. Atoms and genes don’t exist, or may not be able to determine their existence. Our methods of observing them, such as theories and equations, might not need to argue that atoms and genes exist. They only need those theories and equations to hold true given the circumstances of those phenomena. This may be the theory dictating the formation of atoms or a equations determining when a gene activates. An anti-realist might argue that, as the universe supposes no such notion of autonomy on humans, we can exercise an unrestricted autonomy. Our notions of autonomy would then give humans power over machines and scientific theories. This battle between realists and anti-realists has taken place through much of the history of philosophy. Philosopher Thomas Kuhn wrote that discoveries cause paradigm shifts in our knowledge. We experience changes in perception and language itself that allow us to create new scientific theories. This idea that science depends on the history and language of our time contrasts the scientific realism. In contrast, philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein argued for remaining silent on such issues of what science tells. We can avoid some of the conflicts between realists and anti-realists. On gene editing, an anti-realist may argue autonomy depends upon unknowable factors of genes.

Ethicists have to contend with moral realism as well. Moral realism is the idea that moral claims we make depend on other moral components such as obligations, virtues, autonomy, etc. Something like “Murder is wrong” may depend on responsibility to do no harm. It can also be the idea that claims can be true or false and some are true. The first definition is the ontological definition while the second is the semantic definition. Au contraire, moral anti-realists may argue these claims don’t hold such a value. They may also argue that the claims may have the value, but no moral claim is actually true. To a non-philosopher, this might seem trivial. It’s easy to say “Of course moral claims depend upon things like obligations and autonomy!” But reasoning through arguments shows the this difference. A moral realist might argue that objective theoretical values such as autonomy are self-imposed, but not from our own self. Instead, they’re from an idealized version of ourself reflecting upon those values. The moral realist would create a biological-digital autonomy from this idealized notion. It might be ambiguous or impossible to define with complete clarity.

We can improve these methods of reasoning and thinking in areas such as logic or statistical reasoning. We can also determine knowledge of what our scientific theories tell us. Through this, we can create notions of autonomy to address these issues. In addressing these issues, we must identify what philosophical struggles the digital age imposes upon us. Silicon Valley ethicist Shannon Vallor teaches and conducts research on artificial intelligence ethics. In a recent interview with MIND & MACHINE, she spoke about how her students began experiencing cycles of behavior with technology. Students experienced anxieties when jumping into new technologies of smartphones and social networks. These students would become reflective and critical about technology. They would become more selective as time went on. She described a “metamorphosis” as students tried new technologies. They would reflect to understand how they themselves changed as a result of them. This could be with attention span or notions of control similar to autonomy. Throughout the process, the students ask what role the technology has in their lives.

Through human and machine autonomy, Vallor explained how the power to govern our lives relates to these ethical theories. This meant using our intellectual control to make our own choices. AI presents a challenge of the promise of off-loading many of those choices to machines. But, though we give machines values, a machine doesn’t appreciate these values the way humans do. They’re programmed to match patterns in a way that’s completely different from our methods of moral reasoning. The question of how much autonomy we must keep for ourselves so we can maintain the skills of governing ourselves. Being clear, though, Vallor said machines don’t make judgements. Judgements must perceive the world. While machines process data in code, they don’t understand the patterns we perceive as humans. Instead, we have to understand what’s gained and what’s lost in giving that choice to machines. I believe these judgements are exactly how our heuristics about moral reasoning and theories come into play. It’s what separates man from machine.

Artificial intelligence programs, computers, and robots also learn from our biases we instill in them based on how we train them. Vallor expressed concerns of authoritarian influences taking control of artificial intelligence. Still, there are ways to use AI for democratic choices. One example of such an issue was China’s social credit system built on ideas of society built only on social control and social harmony. It uses an all-encompassing AI system to track citizen performance. It serves the centralized standards of behavior with systematic rewards and punishments to ensure people are on a narrow path. Vallor said “we are not helpless unless we decide that we’re helpless.”

One might present objections to these methods of moral reasoning. One might argue that humans are irrational on the basis of behavioral psychology. The biases, false judgements, and poor methods of reasoning that are in our nature from this field show that we rely on heuristics. Falling victim to fallacies such as ad hominem or sunk cost, our methods of reasoning my seem flawed. We can at least create arguments that have some degrees of certainty, though. It may includes the predictions economists and psychologists make of our behavior. I address this argument by arguing that, though our methods of reasoning may have flaws, they can improve. We learn life lessons and proper etiquette about treating people as we gain experience. This suggests that moral reasoning such as on issues of our digital-biological autonomy may improve too.

Still, there are reasons to remain pessimistic about our moral reasoning we derive in this sense. One might argue that our brains developed not to find truth, but to be better than those around us. An evolutionary psychologist may theorize these are social connections of “survival of the fittest.” They haven’t lead us to achieve a more objective truth, but a more effective persuasion. I address this by explaining human beings might have these naturalistic tendencies. But it doesn’t mean that the brain developed to behave in response to these social forces only. If an individual has to convince others to avoid certain dangerous species of animals, it depends on problem solving. This is the method of reasoning by the tribe. The cognitive method of deliberating facts and reflecting upon them shows this reality of our nature. It can apply to moral reasoning.

Another argument could be that our methods of reasoning are only rationalizations, not reasons. They’re only conclusions we want to believe. I illustrate this with how politicians may go to war or limit the rights of certain groups through the solutions. Then, they reason backwards from the solutions such that they contrive justification of them. The ideologies of politics, in general, seek these sorts of conclusions on rights, liberties, and other values. We may find ourselves emphasizing these answers before we have the questions. It amounts to ideology. I address this by arguing we can test rationalizations against observation and intuition to come closer to reasoning. We may have intuitive reasons that we are not able to articulate for every action. But we still may have the ability to form moral judgements about those actions. It’s this intuition about our moral reasoning that we trust to lead us in the right direction.

I have attempted to outline methods of moral reasoning given the constraints of technology. I did this while reckoning with the arguments put forward by philosophers for decades. I hope these notions can prove beneficial to conversations of autonomy and rights of the individuals and machines in the digital age. We must re-evaluate these thoughts to address today’s issues. Artificial intelligence and genetic engineering can seem more similar than they first appear. Through a notion of moral reasoning, determine what this digital-biological autonomy should be.

-

How a 2001 video game warned us about the dangers of artificial intelligence and genetic engineering

The crises of the digital age have brought us concerns about information. The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal raised concerns of privacy. Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election showed this power of information itself. Long before these events, a Japanese video game developer predicted these issues. Hideo Kojima would create a game in which the archenemy was none other than the American government itself in 2001. In what would become the first postmodern video game, Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty showed this dark side of science and technology. In today’s discussion of gene editing and artificial intelligence, the message holds true. Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty for the Playstation 2 continues to be among the best messages about the dangers of our Information Age.

Video games as media help us understand ourselves in simulated universes. Like any work of fiction, video games teach us higher truths about the world but give the player a goal to achieve. In Sons of Liberty, the player uncovered a conspiracy of the Patriots. They were group that manipulates information to control the American government. Later in the game, though, the Patriots became encoded onto data itself. They were then manufactured into a computer program that controls human behavior. The way digital information replaced genetics shed light on current event concerns. Artificial intelligence and genetic engineering show these issues of control over nature and ourselves. The player progressed through the game finding the truths about these stories and uncovering the secrets. This challenge gave the player the control and power to make the right decisions. It set the stage for post-modern elements of truth and reality to come into question. There were other postmodern elements like deceiving the player into thinking they’ve lost and anachronistic characters like vampires. These elements set the stage of distrust and avant-garde, an unusual aesthetic form. The central themes allowed anyone to understand the concerns of this dual genetic-digital issue.

To introduce the theme of the game, I first look at the end. The game’s protagonist Solid Snake proclaimed a dramatic monologue to the player him/herself at the end of the game. Throughout the game, Snake, a genetically engineered soldier, hunted the Patriots. At the end, he realized it was part of a simulation to test human behavior in a society of manipulated information. In his gritty, serious, yet determined voice, Solid Snake declared:Life isn’t just about passing on your genes. We can leave behind much more than just DNA. Through speech, music, literature and movies… what we’ve seen, heard, felt… anger, joy and sorrow… these are the things I will pass on. That’s what I live for. We need to pass the torch, and let our children read our messy and sad history by its light. We have all the magic of the digital age to do that with. The human race will probably come to an end some time, and new species may rule over this planet. Earth may not be forever, but we still have the responsibility to leave what traces of life we can. Building the future and keeping the past alive are one and the same thing.

We face a grim, dismal future with dire fears of climate change, nuclear war, and terrorism. If we don’t live forever, then it might seem to make no difference for us to build a better future. But we must keep the past alive, as Snake emphasized. This history preserves a type of immortality of our work, even if life and humans themselves are temporary.

The player discovered true allegiances, backgrounds, and motives of characters throughout the game. In crafting a narrative about the power of technology, there were two tragedies that illustrate different flaws. The first was the President George Sears, a genetically modified clone. Sears became a terrorist, the game’s primary antagonist. This tragic fall is like the Roman Emperor Nero’s road to tyranny, though debatable. Nero sought to twist truth and history. The fall happened as the Patriots preserved their power in attempting to murder Sears, who wanted to fight for the freedom of information. They did this through the GW System, which announced the tragic themes such as: “Not even natural selection can take place here. The world is being engulfed in ‘truth.’ And this is the way the world ends. Not with a bang, but a whimper.”

The second tragic fall came with Raiden. A rookie who idolized Solid Snake and worked to kill Sears, Raiden represented the player. Raiden’s existential tragedy came as he realized his own military support were not real people. They were only programmed computers. Only at the end, as he threw away his dog tags that have the player’s name on them, did he find freedom from the information that controlled him.

Sears believed life was predetermined by genetic information. He believed he must re-write history and become a terrorist. Nineteenth-century German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche as he wrote in The Birth of a Tragedy would describe it as a Dionysian view of freedom. It broke from common notions of the way a president would act. As Snake proclaimed, we need to develop these new ideas of thinking to address the tyranny of those who control information. These could have represented our fears of artificial intelligence and genetic engineering. Sears’ discovery, as though he were only a pawn in a game, forced him to into these realizations. He understood that old-fashioned ways of thinking lead to a sort of obsolescence of information. It’s like the conflict between today’s news sources and forms of journalism preserving truth and justice against bots on social media pretending to be human. These existential tragedies described these trials of the digital age. The GW system’s name itself referenced George Washington. Sears confirmed this allusion by declaring independence of a new nation on the day, April 30, George Washington took office. It served the themes of existential crises brought to the United States by genetic engineering and artificial intelligence.

Raiden, rather, represented the player, as he was guided through the story by others. He relied on what’s others tell him the same way we, consumers of information do. It’s our methods of making sense of a twisted, confusing world. Raiden loved war games and thought he knew what to do because of this. This also paralleled the player thinking he/she knows what to do by what the game tells them.

In a deconstruction of the video game genre itself, we question the reality that video games create. French philosopher Jacques Derrida in Limited Inc described this deconstruction. It discerned fiction from non-fiction. The same way we test truth from fake news and post-truth politics, Derrida argued to ask “What is non-fiction?” Taking Solid Snake’s speech for granted, Raiden asked this question to free himself. I believe that, if the player found this existential freedom from their own voids of truth and reality, then they, too, won. Coming to terms with the truth of artificial intelligence and genetic engineering, we find freedom. Modern computers today make decisions in their own contexts, and the current trends of genetic engineering push the limits of our precision to change ourselves. The truths are only there insofar as we create them. Solid Snake continued this theme in another monologue:

The memories you have and the role you were assigned are burdens you have to carry. It doesn’t matter if they were real or not. That’s never the point. … There’s no such thing in the world as absolute reality. Most of what they call real is actually fiction. What you think you see is only as real as your brain tells you it is. … Listen, don’t obsess over words so much. Find the meaning behind the words, then decide.

At the time of game’s release, these events paralleled the U.S. military actions. The involvement in Afghanistan and Iraq and creation of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp showed these themes. Given the realistic themes of the game, it’s difficult to not draw comparisons of society through them. For today’s issues, I believe Son’s of Liberty illustrated modern fears of the privacy and technology as a whole. We find meaning behind words the same way we uncover our destinies. This is even if they’re predetermined by genetic engineering or produced by computers. Raiden’s decision to choose his own destiny parallels this, as a genetic-digital duality would.

Postmodern art, as Solid Snake explained, views reality with a smug smirk. It invites the audience find the meaning of words, language, and art themselves. Questioning everything, the player wondered what sort of dark monsters lurk in what’s real and what isn’t. Truth in the Information Age may be elusive. The Facebook-Cambridge Analytica and Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. Presidential elections show this. Solid Snake may have been pessimistic and cynical with his world views, but we can at least take solace that we can understand them. We have the power to meander through the difficulties of truth itself.

-

The immortality of science writing

As I parse through A Field Guide for Science Writers on my Kindle cloud reader, I recognize how science writing is a craft that takes decades to hone. I also begin to hypothesize that, no matter what you write, there are always ways to improve it. In describing how writing differs from other activities, I draw an analogy between writing and immortality. The immortality shows when others are able to read our writing and understand what we wrote at moments later in time. If scribbles in sands are thoughts that succumb to waves, then the etches in concrete are the writing. In this sense, writing has a way to transcend the moment and become something captured at other places in space and time.I draw upon philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s will to life, the way we avoid death and its fears. We can extend this to become a will to immortality. We seek immortality in what they do to overcome the fear and implications of death. We do this through culture, especially the nineteenth-century German culture Nietzsche observed in particular. Professor of Political Science Richard Avramenko wrote, immortality lets us understand the unknowable. In a way, we may know death to pacify it. Avramaneko draws upon Nietzsche’s writing of the fear of death and the unknown that underlie this will to immortality. I believe writing captures this immortality as we produce language free from our mortal selves. The immortality of writing comes through arguing and creating knowledge.

Writing may also share properties with special relativity of physics. This idea of physics concerns how our notions of space and time themselves become warped at speeds near the speed of light. It’s similar to my previous discussion on trauma fiction. We confront this temporal nature of our own lives and thoughts. They comparison to the eternality we give to writing that we confront truth and ideals. When we write, we immortalize our thoughts through language the same way a painter immortalizes their work through brushes and strokes. This explains how writing captures parts of ourself that we choose to present in a form others may interpret. Writing itself could be the vehicle that proves instrumental in carrying people.

Writing is, in itself, tied closely to our thoughts. It’s another form of thinking and shaping who we are as human beings as well as understanding all forms of knowledge about the world. For me, I’ve viewed writing as a source of power at least since I fell in love with philosophy in high school. It was almost a necessity for me to capture my thoughts through appropriate rhetoric and language. I still remember clearly my journal entries and writing samples from freshman year of high school. I critiqued the education system around me and the way students approached learning. Though I fell in love with physics as early as my first semester of high school, I envied the power of writers to critique and formulate arguments in any way they willed. It’s possible that my interests were only naive cynicism and youthful rebellion. I lacked the thorough self-awareness that made writing great. I liked to pretend, though, it was courageous intellectualism in the face of adversity. Regardless, it set the stage for me to bring light to the purpose of education and helping other students with research in college. Though it wasn’t until college when I explored my philosophical interest, the fundamentals of my language and rhetoric have been within me. I sought philosophy for the refined precision to communicate and critique these arguments. The way I’m able to draw such a lengthy narrative, going back to a decade ago, is a testament to this immortality of writing. My reflections on my blogposts from three or four years ago also show this.

Writing about science I can present scientific research itself as immortal. Presenting a story of science means taking those experiences and voices of scientific research and creating a narrative. Hidden messages and truths become apparent. We immortalize science to discover its meaning and value. Other forms of science writing, such as searching for humanistic values and solutions to ethical dilemmas in the work of scientists illustrate the ever-changing, dynamic nature of science. It’s similar to my writing on physician-literary scholar Rita Charon and my older blogposts. Yet, writing about science, the same way we write about anything else, defies that nature. It immortalizes it in some way. Capturing it in a moment of time, though, we understand its true meaning. We can determine the role of artificial intelligence research in computer technology by examining current research. Science writers can portray the messy, nuanced history of fields like psychiatry to bring to light humanistic issues. My writing experience has wrestled with the immortality I’ve given to issues everyone faces. Through this immortal nature of science writing, we can spread the truth and beauty as they are.

-

The science and philosophy of silence

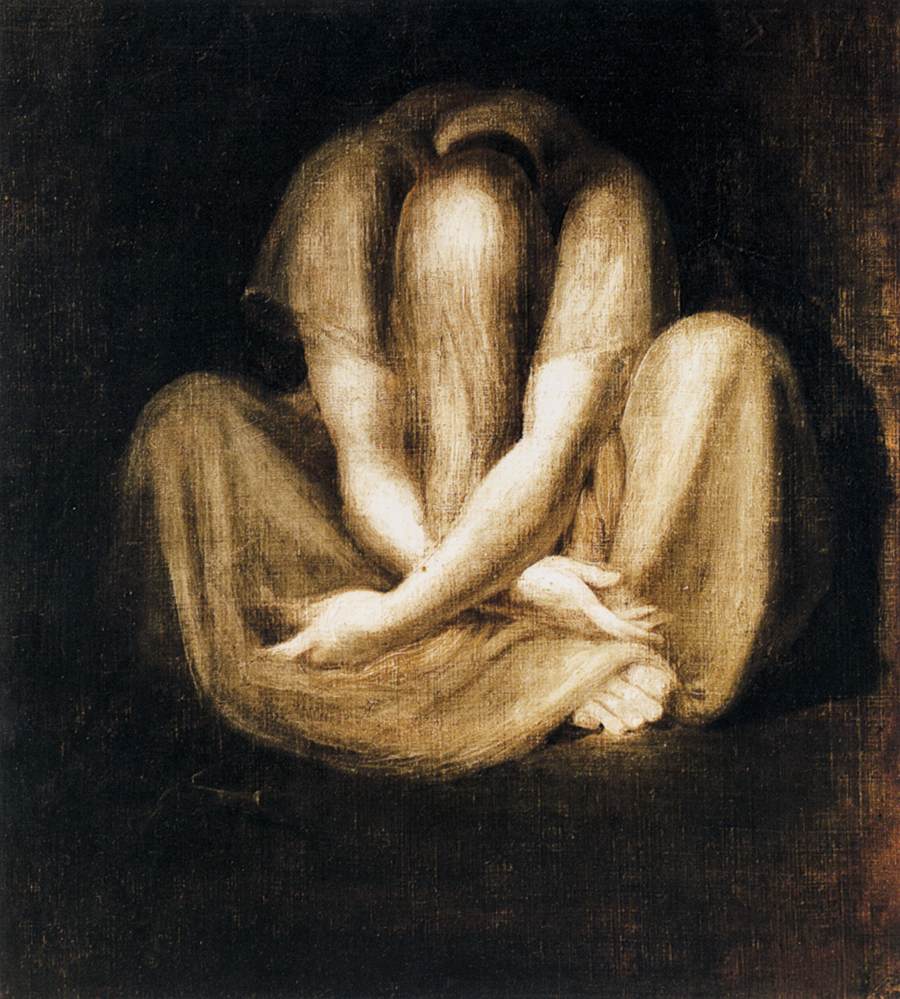

Henry Fuselli’s “Silence” I wake up in the middle of the night. I wake up frequently, actually, because I can barely get any sleep. A solitary prisoner confined to a cell, the night marched on. My comfort is forced to the cold, dank concrete that carried me in and out of sleep. As I dreamt, the world would collapse in on itself leaving me at the hand of my subconscious. The darkness and silence filled the night.

Winter approaches, and, with it, comes the deafening whiteness and frigidity of snow. In these settings, the concept of silence is powerful. Taking breaks from speaking or writing invites the reader to share a moment of silence. Silence in all forms, though is powerful. Even the near-instantaneous full-stops at the ends of sentences and our quiet moments as we process thoughts hold meaning in our rhetoric and art can be filled with introspection of many forms. Composer John Cage’s (approximately) four and a half minutes of silence song forced us to listen to the ambient sound around us and question what we consider music itself. As it shed light on the ways musicians, writers, poets, and other scholars use pauses and breaks, silence of any form reveals these deeper natures within ourselves. Silence is a powerful force that lacks a moral direction in the general sense. For this reason, we can use it for both good and evil as equal as they are in one another.

The wrath of silence comes in many forms. At its worst, people use silence as means of manipulating. We can examine silences like a politician or scholar choosing to remain silent on issues. The allegations of Trump silencing women can show hidden intentions and motives. In some cases, it can produce the ironic result in revealing more than we would otherwise say when we choose to speak. The inexpressibility of horrors like trauma speaks about greater concerns in the individual psyche. Some force others to recognize what they lack the courage to communicate. as many call the “silent treatment,” is abusive, deceitful, and immature. Denying a person’s right to respond to criticism or allegations furthers the sinister nature of silence.In a social sense, isolation, a more personable form of silence, has been shown to have adverse affects on the brain in the way it forms neural connections, according to Neurobiologist Richard Smeyne of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. We can view isolation as a form of silence between individuals in a social network. Through isolation, our thoughts and voices might are silent in a figurative sense, even if we still have the power to speak. This takes forms of pressures among marginalized minority groups and opinions. It may also include isolated scientists who don’t collaborate or communicate with others. Even without pure social isolation, many of us feel loneliness deep within ourselves. It can produce a myriad of mental health issues through its silence of our thoughts and ideas. Individuals suffering from depression often “suffer in silence” with their sheer inexpressibility. I’ve even wondered whether my break from blogging during 2017 and 2018 represented a silence of my soul’s expression. Finally, for legal and social purposes, our methods of solitary confinement exacerbate these detrimental consequences psychologically and neuroscientifically. All these phenomena use silence in one way or another in achieving their ends.

Silence, in other contexts, forms the basis of beauty and harmony. Through music, we wouldn’t have our fundamental concepts of rhythm and dynamics without resting. A painting’s use of white space can reveal greater emphasis on some parts over others. As an example of the latter, newspaper will often use white space between sections and words to draw attention to them and ease readability.

“Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schweigen.” – Ludwig Wittgenstein Austrian-British Philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein used silence to upend philosophical beliefs itself in the 1920’s.He said “Whereof one cannot speak thereof one must be silent,” or as philosopher D. F. Pears translates, “What we cannot speak about we must pass over in silence.” He wrote this in his piece on logic and language, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. When I read the original German text (“Wovon man nicht sprechen kann, darüber muß man schweigen”), I felt an attack on my views of philosophy. I should remain silent? For us to remain silent in areas where we cannot speak seems to upend fundamental views of scientist and philosophers alike. I realized that our ideas of language and logic can only be true when we understand the limits on the power of their claims. This silence the philosopher puts forward is both useful yet apprehensive on knowledge itself.Wittgenstein explained that many philosophical subjective experiences were the only things worth studying. This included poetry and the subject of God. But they carry so much subjectivity that we cannot put forth conclusions about them. Instead, we must remain silent on them. For a philosopher to argue a sort of “let’s not talk about it” position ignited responses and criticism from others. He would continue to share new insights into the relations between world, thought and language. This way, he’d show the nature of philosophy itself.In scientific writing, though, we find a wide gap between the communication of strict, scientific language and popularized, literary jargon for non-scientists. The former resides in our peer-reviewed journals and references while the latter fills the magazines, newspapers, and blogs. I’ve personally struggled in writing about theoretical mathematics and analogies. Even within scientific, theories of quantum mechanics and special relativity need metaphors and analogies. A particle under the laws of quantum theory used to describe atomic interactions lacks a knowable position and momentum. Physicists of the dawn of quantum mechanics like Niels Bohr and Albert Einstein created new ideas of a particle with their theories. The same way a pianist sits in silence or a painter leaves white space on a canvas, scientists recognize limits to assess their arguments.I’ve strived to bring those topics into terms a general audience can understand. I hope to break down the boundaries of science writing itself to further realize them. The limits we recognize on these forms of writing forces us to remain silent. Scientists and writers alike may borrow techniques from other fields to go beyond their original rhetoric. Introducing metaphors to break the mold forces us to acknowledge these boundaries on our scientific methods of naming, such as the limits of the senses that neuroscience can describe. The modern goal of science, complete comprehension only through description of the universe, is unfeasible to achieve.I sit and stare into the abyss without a word to be said. But maybe I’m only at a loss of words. When I choose to stop speaking, the inexpressible wins.

-

Art meets science: the limits and ethics of neuroaesthetics

Beauty is truth, truth beauty, — that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know – John Keats, “Ode to a Grecian Urn”

To some, beauty may be only in the eye of the beholder. But if there were an objective basis for it, researchers have only begun to uncover what it is and what it means. To find a philosophical and scientific basis of art, we can study how our brains respond to aesthetics itself. The humanities and sciences seek different approaches. The humanities are speculative while science is empirical. But both can understand art. We may compare both methods to reveal how our brains process art, aesthetics, and, in some ways, morality. There remains debate among philosophers about Kant’s theories of aesthetics. We can reveal the connection of beauty with epistemology and ethics – from neuroscience, too. The potential for this area of research could hold benefits for art-based therapeutic treatments. It may also help determine art’s relationships to morality and justice and the neuroscientific basis for what it means to be human.Neuroaesthetics, or an empirical, scientific approach to the aesthetics of art, seems appealing. This way, we can argue the way the brain responds to art represents the value of art. Reducing what makes us who we are down to the brain, though, raises issues, as my friend Adam Kruchten wrote. Any sort of experience of art may be nothing except for the way neurons fire and chemical reactions occur. It’s this external stimulus of looking at a painting or listening to music that triggers these bodily responses. But this neuroaesthetics approach has limits. Scientific studies reveal that the neuroscientific, bodily response doesn’t correlate exactly with aesthetic experiences. The truth is that the research reveals those experiences as much more complicated than our empirical evidence can show.Given these limits of the brain, it’s not clear how art itself is relevant to neuroaesthetics. If neuroscience relies on the workings of the brain itself, then how we can create neural representations of works of art? We must subject ourselves, not to a work of art itself, but to pictures of art that from which we can determine how neurons fire. This gives us a neural correlate of these forms of art. We may determine an epistemic path, or the limits of knowledge itself, to create this reduction. It forces us to abandon our encounters of artwork. Instead, we create direct depictions of art through which we study. It explains why my work on re-creating neural responses using external stimuli is so limited in how well I can “read someone’s mind.”We need to describe the limits of the ways our bodies respond to works of art such as paintings or pieces of music. I cite beauty as one method of how art moves us on physical and intellectual levels as a way of determining this bodily response. This comparison has its limits because a bodily movement doesn’t guarantee one finds a work beautiful. Perceiving a work of art as beautiful comes from a harmony among our faculties of cognition. It includes our senses such as auditory and visual parts of the nervous system. Like my previous posts on symmetry and rhythm, this harmony is “purposive without purpose”, according to Kant. This means that the harmony of art has a purpose intended by the artist. But, as we experience the artwork, they should only affect us as if they had purposes even while we don’t find the purpose. This is what makes a work of art “beautiful” and explains how we perceive pleasure from it.

Using beauty to show aesthetic value has its limits. If neuroaesthetics were to gauge beauty of artworks, it should use objective, universalizable methods. We must be careful to universalize our own subjective experience in a way that all people experience. Beauty itself can vary between cultures and groups of people. Art can move the individual without being beautiful, as argued by scientists Bevil R. Conway and Alexander Rehding. There are ways to avoid these issues, though. While the subjective experience itself varies, it has universalizable, objective methods of arguments. Two people may dispute that one work of painting is more beautiful than another. But their methods of deduction rely on objective, nuanced, justified arguments. This could be arguing that there is a certain balance of colors or that the rhythmic symmetry of painting in one is superior to that of another. It’s within these methods of reasoning that beauty emerges, not the subjective eye of the beholder. These methods of reasoning could help neuroaesthetics find a neuroscientific, empirical basis for art. It also explains how we draw moral and ethical judgements from works of art. We may have different movements. Some of us express more shock of pupils dilating at the sight of a sensationalist news headline. But our methods of reasoning provide a fundamental, shared way of communicating. Through this, we draw meaning from such an artistic move. Indeed, scholars have found success in these methods of inquiry. Neuroscientist V.S. Ramachandran and philosopher William Hirstein studied practical rules that connect features of artwork to beauty itself. They described “eight laws of artistic expression.” They include peak shift principle, which is the stronger response to stronger representations of desirable features. The scientists also described grouping, that is, discriminating a figure from the background. The other laws include problem solving, the way we favor the detection of objects through struggle. One may also use symmetry, or complementary objects revealing more information easily.

Kant went deeper in characterizing aesthetic judgments in such ways to address these problems. For Kant, deep aesthetic encounters are states of “disinterested interest.” This means that our judgements of beauty create pleasure, not the other way around. Many have attacked this claim. German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and psychologist Sigmund Freud believed art must relate to will. Political theorist Karl Marx believed all art must be political. The philosophical notion of expressionism views art as a subjective response to the world around us. Still, Kant’s ideas describe a method of how aesthetics is much more concerned with our judgements. We form these judgements in response to art alongside the bodily response we experience. As Kant theorized, art is argument, criticism, and persuasion.This makes the question of determining neural correlates all the more confusing. Neuroscience, as it seems this way, is far too limited in capturing art. In fact, it might be the case that art itself sets the foundation for understanding neuroscience, rather than the other way around. We describe the beauty and elegance of mathematics, physics, and physiology of the processes of the nervous system. From there, those features can be used to explain phenomena that emerge from them.

Kant’s notion of the sublime provides a way of determining a connection between aesthetics and morality. Before the eighteenth century, philosophers claimed the sublime was beauty that left us awe-struck in such a way we couldn’t even measure it. Kant later wrote that sublime even goes beyond form and purpose in a way that we can speak of morality in its terms. The sublime power of Beethoven’s music could describe how it moves audiences to a type of ecstasy. This is beyond the comprehension of their senses. It incites feelings of wonder and romanticism that can only music itself can explain. The sublime also relates to expressions of fear, uncertainty, and terror in art. Kant grounded his moral theory in reason. He described a “moral culture” emerges when our moral faculties of reason create the limits of experiencing the sublime.“Beauty is nothing other than the promise of happiness.” – French writer Stendhal, similar but not the same as Kant’s notion of beauty.To find the neural correlates of art, we probe our senses. Particularly, understanding the sublime gives us greater meaning. I finish with a discussion of the sublime among philosophers Amir Aczel and Sandra Shapshay, English professors Paul Fry and Alan Richardson, and conductor James Judd. In the YouTube video The Sublime Experience, they discussed how the sublime through all forms of art and religion provide the grounds for differentiating between pleasure. The scholars debated notions of beauty, greatness, picturesque, infinity and other features of art. These ideas relate to our arguments in religion and philosophy.

Shapshay emphasized the distinction between the mathematical and dynamical forms of sublime. The mathematical is size overwhelming us, such as staring into the sheer immensity of the universe. For the dynamical, the force overwhelms us, as in how the horrors of war shape a country. Philosopher Robert Clewis argued there’s even a third form, the moral. He described this in his book The Kantian Sublime and the Revelation of Freedom. Neuroscientists Tomohiro Ishizi and Semir Zeki argued these sublime and beautiful features have brain activity patterns. Despite the limits of the relationship of neuroscience and art, this empirical evidence shows how we surpass our senses. We can reveal the deeper connection between neuroscience and art. We may study these empirical phenomena alongside speculative rhetoric of art and ethics hand in hand. It provides a more nuanced, inquiry of what makes us human.

-

The science, mathematics, and philosophy of rhythm

Zebra finches use a “critic” in the brain to differentiate between the rhythm of songs of other birds and, through this, learn songs. Like the ebb and flow of the ocean,

A rhythm emerges from the pen,

I capture it, imagine it,before it disappears.

Appropriate rhythm in writing means making sense of the relation between words and phrases. Stress, repetition, fluctuation, rhyme, meter, pattern, juxtaposition, and harmony all come together. These form the aesthetic and intellectual properties of rhythm. For a philosopher studying semantics or neuroscientist uncovering our nature, rhythm poses challenges. I’ve written on the subject with respect to symmetry. Let’s delve into rhythm’s secrets philosophically, mathematically, and scientifically.

Through much of my scientific writing, I pay close attention to how lengthy my sentences are. Too many long sentences at once can lose the reader in monotonous, cumbersome passages. I especially fall into this trap with description and exposition. Long sentences bore the reader. Short, astute sentences can feel abrasive and clumsy. We alternate between the brevity of Twitter to the nuance of academic prose. it’s easy to succumb to habits and forget about the appropriate rhythm with which to write. Rhythm is both something we plan in advance and re-evaluate through reflection and speculation.In the realm of aesthetics, philosophers have debated the role of rhythm since the Classical era. In Book III of Plato’s The Republic, Socrates clarified that rhythm and meter are what separate poetry from pure prose. Pre-Medieval philosopher St. Augustine developed a theory of aesthetics based on ideas of rhythm in De Musica. In congruence with the theologian’s religious beliefs, God is the origin of rhythm. We discover these mathematical truths, pre-determined by God, of rhythm. It’s like how Plato believed humans collectively remembered them.

Emerson’s poem “Merlin” showed the use of rhyme and meter to create rhythm. Particularly the lines that moved back and forth between his own sensations and the way to craft meters of poetry from them showed this. Emerson in this section, showed how the rhyme fit so naturally that it seems like part of human prose. Socrates’ idea of rhyme and meter separate prose from poetry lets Emerson use this distilled rhythm.Thy trivial harp will never please

Or fill my craving ear;

Its chords should ring as blows the breeze,

Free, peremptory, clear.

No jingling serenader’s art,

Nor tinkle of piano strings,

Can make the wild blood start

In its mystic springs.

We teach ourselves rules and tips on creating great writing to take into account the effect of the rhythm on the piece. To imagine and care for these aspects of the reader gives the writing a property only observed at a scale larger than individual words. Rhythm comes from how words interact with each other, yet remains limited by our conventions of writing. It emerges when you take a step back from your computer screen and look at the whole picture. Rhythm is this frequency. Time itself limits these perceptions as we read. As such, it reveals deeper features of our subjective perceptions, such as the stress, intonation, and tempo of speech itself. Yet we speak of it as something deeper than the combined intrinsic content of words themselves. In this sense, it’s like an emergent phenomena, much like evolution selecting certain genetic traits.

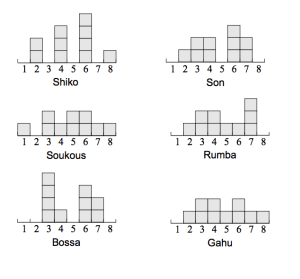

What makes these six clave patterns fundamental are that they reveal maximally even rhythms and maximum sum of pairwise distances between the points as vertices on a tetrahedron. In a scientific context, we rely on our empirical observations of rhythm to determine higher truths of rhythm. Canadian computer scientist Godfried Toussaint finds this connection between shape and musical rhythm. Due to the evenness of six musical clave patterns, they have mathematical significance. That a mathematical algorithm could generate music raises questions about what is music. It raises questions as what sort of mathematical or empirical technique governs what “good” rhythm sounds like.

Placing the six intervals in histogram form reveal patterns among themselves that may dictate the nature of rhythm as a whole. We can find fundamental features among strings of numbers such that the patterns of these features give rise to Euclidean rhythms. These are rhythms created by Euclidean distance, or the straight line distance between the points when arranged in a circle. The numbers show the span between the beginning of successive notes and, thus, represent the simplest way to represent rhythm. This needs much more empirical evidence before showings its truth in all music. Toussaint’s claim that Euclidean rhythms that are reverse Euclidean strings appear to have a much wider appeal. French mathematician Jean-Paul Allouche showed these strings of numbers are like combinations of words. Other mathematicians and computer scientists have developed Euclidean rhythms from Euclidean strings. Toussaint argues that the Euclidean algorithm finds the greatest common divisor of two numbers. It can generate rhythm timelines by using the two numbers as an input to the Euclidean algorithm. The two numbers would dictate the beginning of each note in the rhythm and the span between notes.

In the field of cognitive neuroscience, we can study the ways humans and other organisms produce and test rhythms. Computational neuroscientists Kenji Doya and Terrence J. Sejnowski discovered a “critic” within the zebra finch brain. It lets the finch to differentiate between songs. NMDA receptors, a specific method of chemical signaling in nerve cells, activate to let bird to learn the “correct” song. Scientists Philipp Norton and Constance Scharff found patterns between the nerve and muscle cells. They corresponded with elements of notes and duration of the notes themselves. This is like Toussaint’s study of the beginning of each note determining rhythm. It includes the span between them, both fundamental components of rhythm. This research holds value for finding similar discoveries in the human basis of rhythm as well.

Much the same way a poet translates nature into word, a scientist would find quantifiable metrics of music. They may raise questions for musicology, geometry, and, with enough empirical evidence, neuroscience. Now take a deep breath and let the waves beat upon the seashore. Detect the rhythm and move along like before.

Sources

Doya, Kenji & Terrence J. Sejnowski (1999). The New Cognitive Neurosciences. II. MIT Press. pp. 469–482.

G. T. Toussaint, “The Euclidean algorithm generates traditional musical rhythms“, Proceedings of BRIDGES: Mathematical Connections in Art, Music, and Science, Banff, Alberta, Canada, July 31 to August 3, 2005, pp. 47–56.

Norton, Philipp & Constance Scharff (2016). “Bird Song Metronomics”: Isochronous Organization of Zebra Finch Song Rhythm. Frontiers in Neuroscience.

-

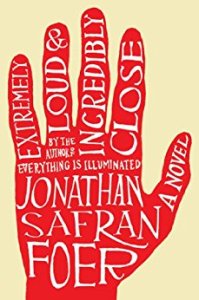

"Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close": Science, aesthetics, and ethics of trauma fiction

.jpg)

Picasso’s “Le coq saigné”, painted in France in the mid-20th century could be seen as a response to the traumatic events of World War II. It’s miraculous that after two world wars, a Holocaust, and a cold war, “trauma fiction” was only coined in the 1990’s. Trauma is fascinating, whether it’s sexual, verbal, physical, or another form. It could be a force that captures all parts of an individual. Someone undergoing trauma could have their senses and perceptions changed in such a way they question fundamental tenets of themselves. They may experience distrust, fear, and anxiety throughout other experiences. When one tries to write about trauma, it’s not uncommon that languages fails them. How can someone write about such a paralyzed, numb state? What sort of description can do justice to trauma while remaining objectively detached? And trauma itself can force an individual to re-examine moments of their life that they can’t seem to shake off. For fiction writers searching for narratives and themes, there are ways of identifying key concepts of trauma. Instead of focusing on what happened in the past, it’s important to understand why we remember those things.

Comparing trauma to a means of survival allows one to view reactions to different psychologically difficult experiences as having some sort of reason to them. Jonathan Foer’s 2005 novel Extremely Loud & Incredibly Close takes a creative, near-experimental approach to the American trauma of 9/11. The novel’s protagonist, a nine-year-old genius Oskar, struggles with the truth of the world after losing his father to the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center. When I read the book in high school, I admired Oskar’s introspective abilities for a child with a severe form of suffering. Yet I felt as though my AP Literature and Composition class didn’t quite capture the true ethical dilemma inherent within Oskar.The magical realism of the novel shows how it is created with techniques that don’t adhere to common realist notions of reality. Instead, the protagonists strategies of dealing with trauma bring him a sense of ethical assertion of the obvious immorality of the terrorist attacks. Oskar’s meaning creates a criticism of political terrorism.

For Foer to write about 9/11, even four years after it happened, was a risk. In the wake of 9/11 many radio stations, television broadcasts, and even movie theaters avoided showing terrorism or terrorism-related media. But Foer’s attempt to capture a mind with post-traumatic syndrome with such detail shows how trauma causes the mind to repeatedly experience and re-experience events of its past until the mind fully understands it. In re-examining the past, the mind enters fantasy and, in this case, a form of magical realism as it relies on memory and repeatedly encountering past events. The reader is left to wonder whether Oskar’s remembrance of the event is real or solely exists in his mind. Foer even uses creative techniques of writing by showing pages that have multiple letters and words written over them (and over them and over them) in such a way they parallel the memories of crashing of the planes into the towers. Or the rumination of trauma. Over and over again. Or the rumination of trauma. Over and over again. Disrupting his sense of time (and possibly space, too), Foer uses a mythic mood reminiscent of modernist literature like T.S. Eliot and Gabriel García Márquez.

Speaking of time and space, Oskar’s deep interest in theoretical physics lets him draw parallels between the past and the present. In fact, it wasn’t until I entered university and began studying physics and philosophy that I saw the extremely close parallels between physics and trauma. As I read Hawking’s physics “story” A Brief History of Time as well as Alan Lightman’s provocative novel Einstein’s Dreams, I realized the components to the significance of Oskar’s interest in physics. Foer invokes the laws of special relativity and quantum physics to demonstrate that Oskar had a keen interest in the fantasy of what lies beyond our senses. In an effort to unify gravity with quantum mechanics, scientists posited an “imaginary” time that is inherent to the directions of space-time, that is, a way of proceeding through time not with the “classical” conventions of steady, unstoppable, linearity. With this “imaginary time”, you can move in circles, backward, and in whatever direction your mind chooses to. It leads to philosophical questions such as difficulty in knowing the future while we have complete certainty of the past and what is the true difference between the past and the future. It also creates a form of magical realism in which the features of PTSD become our way of surviving in a chaotic, unforgiving universe. Moreover, Foer shares how Oskar studied the physicist Stephen Hawking and his three arrows of time according to the laws of entropy. The first is the easiest to grasp: our psychological understanding of time from past to future. The second is the thermodynamic arrow of time that moves from the past to the future, which dictates how systems of energy progress as the universe expands. This explains why an ice cube outside in the sun melts or why we need Carnot cycles to create engines to use energy. The third is the cosmological time of how the universe is currently expanding. Oskar draws upon this research to wonder how he may travel backwards in time, but, because the three arrows must point in the same direction, it isn’t possible. Foer is by no means the next Stephen Hawking, but his knowledge of physics allow him to incorporate a sort of “mythic” idea of science fiction – events governed by fantasy elements while still grounded in a reality of scientific inquiry.

This brings us to the deeper ethical dilemmas of trauma. As part of a greater collection of works Trauma Fiction (by writer Anne Whitehead), Professor of English Cathy Caruth explains that the structure of trauma is a disruption of history or temporality (similar to Oskar’s disruption of space and time) and, as a result, not fully experienced by the victim at the time. For this reason, trauma can cause people to experience persistent and unwelcome thoughts in the future, malignantly effecting recall and recollection. In neurologist Sigmund Freud’s 1939 nonfiction work “Moses and Monotheism”, the relation between “Man” the problem of becoming human is explored. Freud claims Moses was born to Egyptian nobility and his few followers decided to kill him in rebellion. These rebels would later experience incredible remorse for their action after Moses fused with Yahweh, they would create the “Messiah” in their hopes Moses would return as their savior. This controversial story explores how the material reality of the unconscious can be transmitted from one generation to the next through language in such a way that future generations are forced to deal with an uncomfortable, traumatic knowledge. Yet it would create the language and grounds for discussing trauma and memory for decades to come. In her book, Trauma: A Genealogy, writer Ruth Leys explains that this work by Freud is a place of investigation for memory, trauma, and history that is central to discussions of postmodernism and the Holocaust. By virtue of its inter-textuality and despite its recurrent historicist motifs, Freud’s Moses has also enthralled leading figures in French post-modernist philosophy, who have highlighted its importance for the writing of history, the concepts of suffering and the preservation of experience. Caruth comments, in her her account of psychoanalysis and literature Unclaimed Experience, the story is “a renewal of some of Freud’s earliest thinking on trauma is indicated by his use of the figure of the “incubation period” to describe traumatic latency; Freud had used this figure in his early writing in Studies on Hysteria (1895)”. A sort of incubation period is exactly how Oskar suffers to determine, as a theoretical physicist might, the true nature in our universe. In it, as the deep psychological forces underlying the individual take control, the fear, anxiety, paranoia, obsessiveness, and other dark parts of human nature take root.

Freud makes the universality of trauma simple: Trauma seals the fate of man. The cause of our individual psychological difficulties have three salient features, Freud argues: they take place in early childhood, they’re generally avoided through other memories (that attempt to “screen” out the individual’s feelings), and traumatic impressions are generally sexual and aggressive as they attack the ego. Whitehead claims that trauma requires a non-linear literary form through abrupt or immediately self-evident methods. This trauma is usually dormant in which the symptoms are not shown until a later traumatic event in the individual’s life. As Caruth writes, “The experience of the soldier faced with sudden and massive death around him, for example, who suffers this sight in a numbed state, only to relive it later on in repeated nightmares, is a central and recurring image of trauma in our century” (in Unclaimed Experience). We’re not only haunted by the events of our past, but our own psychological difficulty in understanding those events.

Similar to Oskar’s detachment and disillusion of the world around him after his father’s death, the protagonist undergoes existential crises through his efforts in school and other areas of life. Foer disrupts space, time, and spacetime to show the obsessive, haunting feelings that plague the psyche. From these understandings of trauma, Caruth argues, with the case of trauma fiction, the individual undergoes a “crisis of truth” that extends to the individual’s society and peers. Whitehead further illustrates trauma fiction with her point that the ethical questions raised by the individual’s testimony have an inherent literary feature to them as a result of these sufferings.I absolutely despised reading the novel Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close in high school. I felt as though the narrator was too self-absorbed and couldn’t relate to him much. But now I look back on it with fondness. My English teacher emphasized the importance of taking apart an argument with all its assumptions and methods of reasoning when writing. That value and importance he gave me lead me to study philosophy in college as well as taking apart many other truths and ideals of this world. But I still worry that, despite the humanistic visions Foer had for his novel, these methods of literary can leave us staring at mental health patients as though they were fish in an aquarium. We’re distant and detached from their true suffering as we generalize and conceptualize the traumatic framework. For this reason, it’s important for us to remember in all our arguments, there is always a significant subjective, humane element in trauma. People react to problems differently and the way they affect our world views can sometimes be unpredictable and messy.

No matter our literary, scientific, and philosophical efforts, we can’t turn back time. Foer tries, though, at the end of the novel to share images of a 9/11 jumper in reverse order. This slideshow gives the image that the person is not only moving backwards in time, but flying as though they were an angel ascending in their fantasy. A stark contrast to the horror of witnessing suicide, it at least gives the reader a sort of escapism from the trauma. Like all traumatic events, be them historical, psychological, sexual, or of any form in nature, the past remain unchanged. Still, we can turn to science, literature, and philosophy in creating these narratives for the betterment of the future. I’m not looking back in anger.

-

"Overcoming my fear of poetry"

No! I won’t! I won’t write a poem!

You can’t make me! Nor will I succumb to my desires. No, no, no…

I’m a researcher. That’s right. I seek knowledge and certainty. I seek soundness and completeness. I seek objective truths.

For I see the world in black and white. Atop a ship in a sea of gray,

In absolutes, in truth and beauty I can describe the world.

Still, the mighty roar of the foggy ocean, surrounds me on all sides,

through its cloudy mist light cannot penetrate. I fear what lies beneath the surface.

Einstein was the wisest man alive, as science gives us answers,

or Aristotle, a thinker like no other, with philosophy, more questions,

I search for land, refuge from an infinite sea. I won’t read Coleridge or Whitman or Thoreau.

I’ll remain willfully blind to what can’t be described or learned.

I choose not to forsake my judgement in rhetoric and logic,

lest I should become overpowered by my desires within.

I won’t. I’ll lock the chest and throw away the key.

You won’t get a poem out of me.

-

Stoicism to improve your life

“All cruelty springs from weakness.” – Seneca the Younger Philosophy, not solely confined to the writing of academics, can, in some ways, be seen as a way of living. For people to turn to philosophy for the answers to their common struggles and for ways of improving their life isn’t as far-fetched as it would initially seem when one studies the role philosophy had for the Ancient Greeks and Romans. For many Americans, Stoicisms holds answers, yet still remains an incomplete explanation of an individuals’ relationship with emotions.

Stoicism (with a capital S) refers to a set of philosophical beliefs by scholars of Ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoic philosophers emphasizes that “virtue is the only good,” and humans should act in accordance with their health, money, and leisurely activities in virtuous manners. What many people pick up on today, though, is the relationship between Stoicism and emotion: one that emphasizes acting in accordance with “nature” and avoiding destructive emotions that are caused my faulty judgements. The virtue that one seeks is found by placing one’s will in agreement with nature, and, the virtuous person would find themselves free from anger, envy, wrath, greed, and other malevolent feelings. In contrast to the more colloquial “stoic” (with a lowercase S), one is not forbidden from expression emotions at all, though. Only those in accordance with virtues and in agreement with nature should one exercise.

Through its many interpretations and revivals between the Greek and Roman civilizations, people could find a sense of meaning and order in an increasingly confusing and twisted world. Even in today’s era of post-truth discourse and distrust of any forms of media and education, one might choose a worldview driven by the Stoic desire to abandon all unnatural forces and chaos and, instead, live humbly with nature. The rise of the importance of autonomy and agency in progressive movements over the past century could even be argued as causes for these modern-day Stoics to believe they have the power to make decisions for themselves despite unstoppable, immovable forces.

Many contemporary thinkers, even scholars with training in the social sciences, have turned to the Stoic philosophy. Today’s thinkers and writers emphasize citizens to adopt these Stoic principles to overcome their difficulties and remain strong through times of darkness. Some recent examples include a selected set of discourses, How to Be Free: An Ancient Guide to the Stoic Life and philosopher Massimo Pigliucci’s How to Be a Stoic: Using Ancient Philosophy to Live a Modern Life. Pigliucci draws from his own personal experiences and creates judgements on objective grounds such that he can create a style of living and philosophizing for readers to live moral lives. Even writers on creativity tell us secrets and tips of Stoic scholars to unlock our true potential, such as Paul Jun’s article “The Stoic: 9 Principles to Help You Keep Calm in Chaos.” And, falling into more self-help based learning, Donald Robertson’s Stoicism and the Art of Happiness have proven popular among the general public. Cognitive behavioral therapists Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck(and individuals seeking self-therapeutic methods), can’t change the world, but they can help people change their outlook. The Pathak-Wieten Stoicism Ideology Scale itself holds the potential to gauge an individual’s health. American writer Larry Wallace calls Stoicism a mind-hack. We can look up to Marcus Aurelius and his fortitude in trying to break through to his own self and understand how the forces in the world are. All were equal, from ruler to slave, under these Stoic beliefs. Even I, in writing memoirs about my life experiences and struggles, often appeal to my education in Stoic philosophy in overcoming difficulties that outside of my control.

It seems enticing. Prima facie, the idea that people can only face their struggles of things that are in their own control and that they should abandon all else could motivate just about anyone. It seems to toughen people up so that they forget about things that they can’t control. In a way, it’s a cool detachment that can help people understand the darkness. It makes anyone feel that their actions and beliefs are grounded in objective views of the world as they live in accordance with Nature. You also get to call yourself a Stoic, which sounds really cool. Who wouldn’t want to look up to figures like Marcus Aurelius or Seneca the Younger?

Yet, Stoicism, like many other ways of thinking, has its shortcoming. It can be immoral for one to show attachment of love or affection to anyone in their life if they choose to live on a path of nature. The way Stoics choose to forego certain pleasures, lest they risk falling to dangerous emotions, can mean they aren’t able to form the necessary and beneficial attachments as a human being.

Greek Stoic philosopher Epictetus uses a simile of a passenger aboard a shift moving at the hands of nature itself to describe the tricky situation brought upon by Stoicism. The Stoic passenger would have to solely move in accordance with that ship and follow wherever it sets sail. He or she wouldn’t even be able to bring aboard family members, large amounts of food, or anything else they treasured. This simile, though prosaic and simplified, illustrates how Stoic philosophers may give in to forces of slavery, impassioned by their own feelings and at a loss of being able to act in accordance with them. Without even looking towards their fear of death, a Stoic might even choose to die rather than suffer existence.

Stoicism is also at odds with the writing of several Existentialism scholars. Philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche argued that Stoics fell to the naturalistic fallacy, that one assumes that something natural is good on the grounds that it is natural. It’s easy to see how this “natural” justification could run into issues with findings of evolutionary biology and their implications on human nature. It’s very troublesome for one to assume that all of our genetic predispositions of actions related to sex, societal norms, and visceral emotions (such as disgust, fear, distrust, etc.) are all natural, normal, and moral. Would we then justify racism on the grounds it’s natural to fear people who are different than us? Other implications like our sexual tendencies could be used to give a moral excuse to acts of sexual assault.

“But what is philosophy? Does it not mean making preparation to meet the things that come upon us?” – Epictetus (Discourses 3.10.6, trans. Oldfather) Finally, I’m very skeptical of cognitive behavioral therapy and mind-hacks in general. I haven’t seen the appropriate evidence to show that cognitive behavioral therapy is an effective form of therapy and much of the evidence I’ve seen don’t show enough methods of cognitive behavioral therapy to prove it’s effective. I don’t trust mind-hacks as appropriate ways or methods to making one’s life or experience better as I’m a firm believer that deliberate reflection and introspection is a much more suitable method. Any philosophy that is promising to lift your mind and make your life better should be examined with a dubious skepticism, especially one that falls on simplistic truths such as changing your worldview and losing a grasp of one’s emotions. Despite theses limitations and disadvantages, one can’t help but admire the strength and perseverance of Stoic philosophers and how that has helped many Americans find peace with themselves. Maybe, even if people don’t capture exactly what the Greek and Roman Stoic philosophers envisioned, they can find a glimpse of it.